Antoni Gaudí

The Man Who Sculpted Dreams from Stone

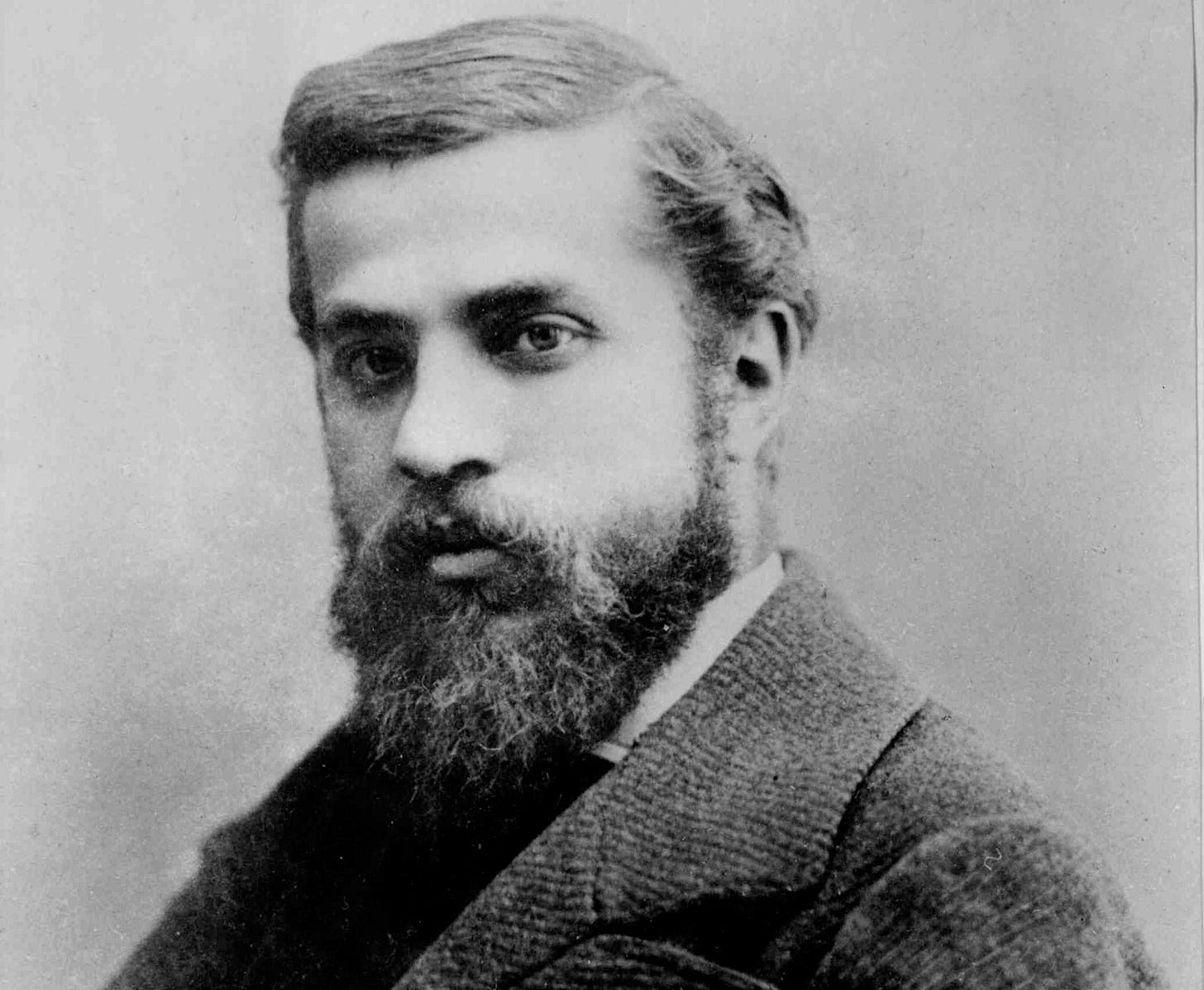

On June 25, 1852, in the sun-bleached town of Reus, Catalonia, a boy was born who would one day teach stone how to move.

Antoni Gaudí was more than just an architect. He was a mystic engineer, a poet of form whose buildings hum with the rhythm of nature. Though his name is now synonymous with Barcelona, the full tapestry of his life and legacy is stranger, subtler, and far more human than the postcards suggest.

A Childhood of Curves and Curiosities

Gaudí grew up observing the world. Often ill, he spent long hours studying plants, snail shells, and bones—not as a naturalist but as someone searching for form in function. These shapes would become the grammar of his architectural language.

Nature, he later wrote, was “the only book worth reading.”

His father was a coppersmith, which gave him a visceral understanding of craftsmanship that no classroom could provide. At the Provincial School of Architecture in Barcelona, he struggled with traditional academics but dazzled with his draftsmanship. His professors, bewildered by his radical ideas, famously quipped:

“We have given a degree to either a madman or a genius.”

Patronage with Purpose

Early commissions like the lampposts of Plaça Reial hinted at his aesthetic: fluid, organic, defiant. But it was his partnership with industrialist Eusebi Güell that lit the spark of legacy. Together, they created full-bodied artistic experiments.

Palau Güell (1888), for instance, is often overshadowed by Park Güell but deserves deeper attention. Behind its fortress-like façade lies a labyrinth of iron and stone that bends light like glass. It's moody, imaginative, and theatrical.

More Than Modernisme

Gaudí is typically classified under Catalan Modernisme. He infused Gothic, Moorish, and even oriental elements with a scientist’s curiosity and a mystic’s devotion. At Casa Batlló (1906), walls ripple like water and balconies evoke bone—an underwater skeleton made habitable.

At Casa Vicens (1885), his first major commission, Islamic motifs and blazing ceramics collide in a festival of color.

Yet Gaudí also built schools (like the Sagrada Família’s workers’ school), furniture, and even religious vestments. He didn’t separate architecture from daily life—he blurred the boundary until living felt sacred.

The Cathedral of the Century

The Sagrada Família was his life’s great romance and obsession. Assigned the project in 1883, he transformed the half-formed Gothic revival church into a sprawling hymn to nature and faith.

Gaudí believed architecture should mimic the laws of nature: branches become buttresses, tree trunks morph into columns, and sun filters through stained glass like light through a forest canopy.

He embraced catenary arches, a form modeled with suspended string and weights, allowing him to design gravity-defying curves with effortless grace.

Every surface served a purpose, every texture a meaning.

What few realize is just how improvisational Gaudí’s process was. He rarely worked with formal plans, preferring to model in clay and adjust on-site. For the Sagrada Família, he lived in a workshop beside the basilica for over a decade, eating simply, sleeping little, consumed by his vision.

Cultural Canvas is a reader-supported publication. Every like, comment, share, and donation helps us grow—your support truly matters!

Light, Color, Silence

Beyond the grandeur, Gaudí had a delicate obsession: light. He studied how it shifted through trees, flickered on water, glowed behind leaves. His buildings embrace the sun rather than shield from it. Windows were placed to allow the day to paint the walls.

Even his use of color was strategic. In Casa Milà (La Pedrera), he softened the stone with iron balconies that writhe like vines, their shadows changing character across the day.

A Personal Life Unbuilt

Gaudí’s solitude is rarely discussed, yet it shaped his work deeply. After a youthful heartbreak, he never married. Over time, he withdrew from society, dressing in worn clothes, sleeping among tools and drawings.

Despite his fame, he lived humbly, sometimes mistaken for a beggar in his final years.

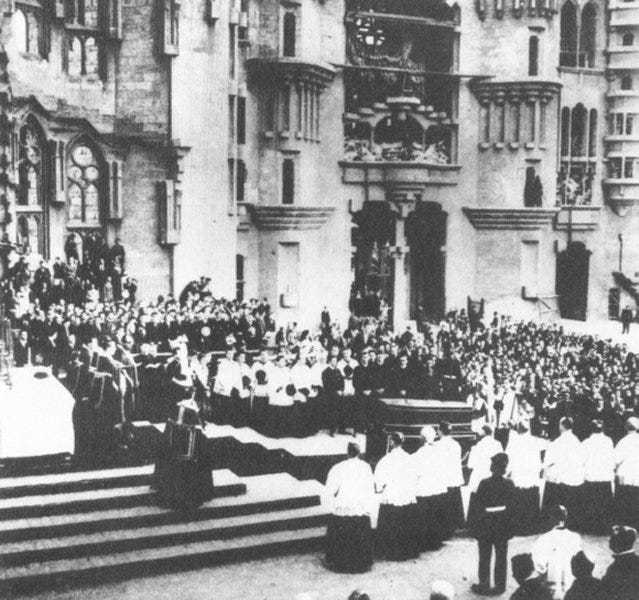

When he was struck by a tram in 1926, hospitals hesitated to treat him, not realizing who he was. He died three days later, aged 73.

The city he reshaped mourned collectively. His tomb lies in the unfinished crypt of his masterpiece.

The Quiet Legacy

Gaudí completed only 17 buildings, but each one is a world unto itself. Seven are now UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Yet some of his lesser-known projects, like the Episcopal Palace in Astorga or the crypt of Colònia Güell, still whisper with genius.

In our age of sleek minimalism, Gaudí reminds us that architecture can still astonish. It can be emotional, allegorical, and alive. His work tells us that imagination isn't ornamental—it's elemental.

As the Sagrada Família nears completion in 2026, nearly a century after his death, perhaps we can finally see not just the spectacle, but the soul behind it.

Missed our last story? Read it here!

Don’t miss the newest episode of our Classic Chapters podcast!

Thank you for being part of Cultural Canvas! If you love what we do, consider supporting us to keep it free for everyone. Stay inspired and see you in the next post!