Caravaggio’s Rival and a Hot Mess

A battle of light and shadow, beauty and raw realism—this was Baroque at its finest.

Born in 1575 in Bologna, he crafted visions of saints and angels so luminous, so exquisite that they seemed to step off the canvas. Yet, beneath was a man defined by contradictions.

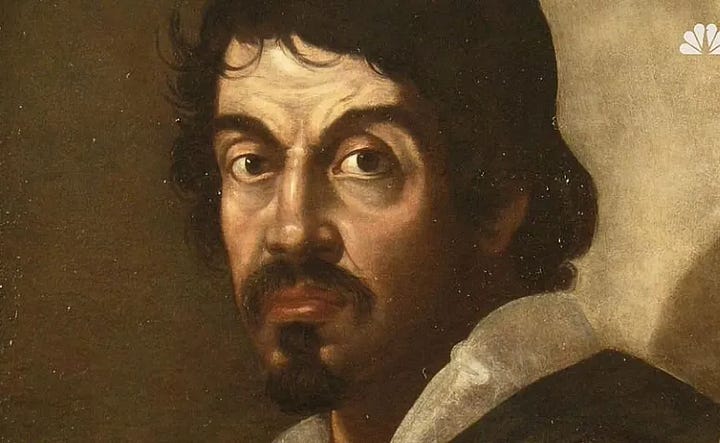

Guido Reni — flawed, ambitious, and locked in a fierce rivalry with Caravaggio.

Their competing styles, their artistic tensions, and Reni’s own complexities form a story far removed from the standard history book. This is a deeper look at his life, his conflicts with Caravaggio, their defining differences, and the lesser-known facets of Reni’s character.

From Bologna to Baroque Eminence

Reni grew up in Bologna, a city buzzing with art and ideas. His dad was a musician, probably hoping Guido would pick up a violin, but by nine, he was apprenticed to Denis Calvaert, a Flemish painter, teaching him the secrets of the Renaissance.

Reni was a quick study, but he wanted more.

He joined the Carracci academy and by his twenties, he had established himself, producing works such as The Crowning with Thorns, a composition marked by dramatic intensity, meticulous execution, and the emotional depth that would define his style.

Bologna was his launchpad, but Rome was where the real action was, and by 1600, Reni was there, ready to make his mark.

The problem was, Caravaggio was already stealing the spotlight.

A Clash of Artistic Philosophies: Reni and Caravaggio

Caravaggio was a walking scandal. His style, chiaroscuro, with its dramatic light and shadow, made paintings like The Calling of St. Matthew (1600) feel like gritty film stills.

He used real people, tavern drunks, sex workers, as models for saints and Madonnas, and his life was just as raw: bar fights, a murder charge, and a knack for trouble.

Reni was the polar opposite.

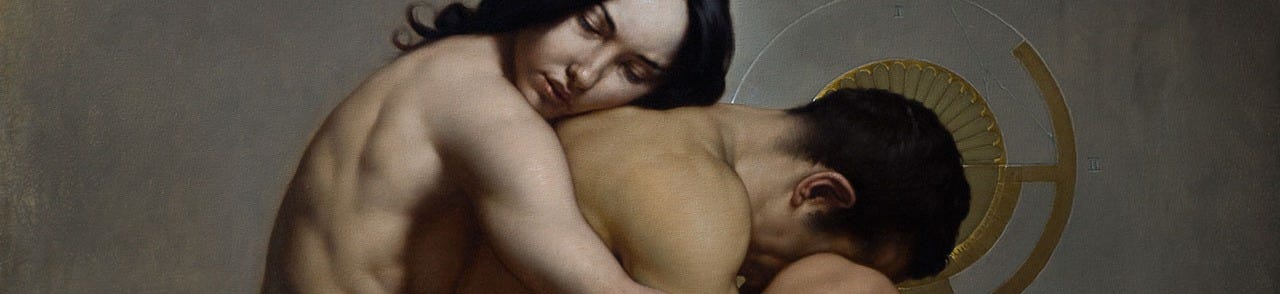

His work, like Atalanta and Hippomenes (1618), was all about idealized beauty, with soft lines, radiant colors, and figures so divine they seemed to float.

The two were like fire and ice, and Rome’s elite loved the drama, pitting them against each other for commissions.

The rivalry wasn’t just professional, it felt personal.

Word on the street was that Reni thought Caravaggio’s gritty realism was crude, while Caravaggio probably saw Reni’s polished style as too safe, too pretty. The Borghese family, along with other wealthy patrons, fueled the rivalry, offering commissions that forced them into a silent duel on canvas.

Yet beneath their stark differences lay a thread of commonality.

Both were masters of drama, whether through the visceral agony of Reni’s Massacre of the Innocents (1611) or the violent tension of Caravaggio’s Judith Beheading Holofernes (1599). Both understood the power of light as a narrative force, though Caravaggio wielded it with brutal contrast while Reni softened it into a celestial glow.

Some accounts suggest that Reni absorbed elements of Caravaggio’s technique, refining them within his own artistic vision, though he would never admit to such influence.

Reni Beyond the Canvas: Gambler, Zealot, and Total Diva

Reni wasn’t just Caravaggio’s rival, he was a character. For one, he was a hardcore gambler, blowing cash on cards and dice like it was his job.

Those stunning altarpieces? Some were painted to pay off debts, not just to glorify God.

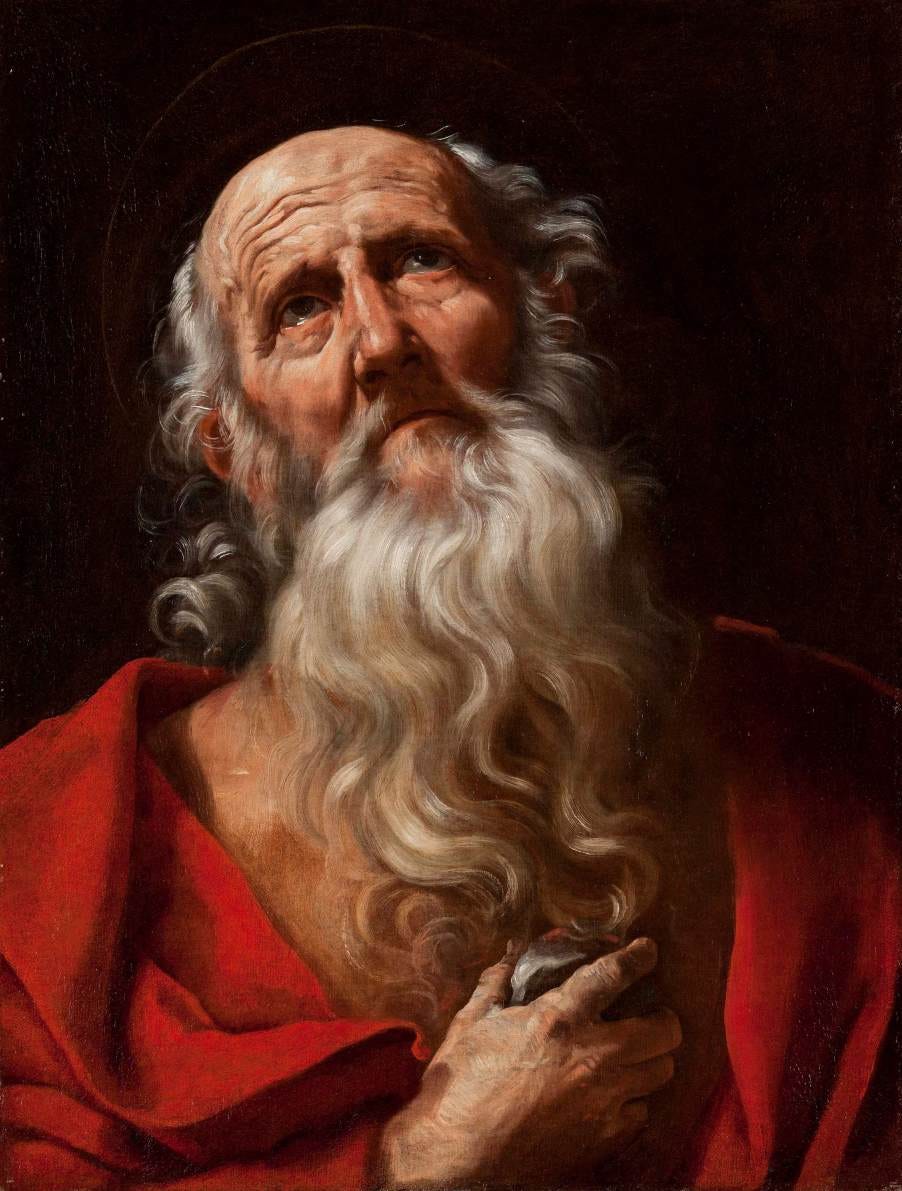

Picture Reni, fresh off a losing streak, pouring his energy into St. Jerome (1605), a work infused with quiet intensity, as if he were channeling his own turmoil into the saint’s contemplation.

It’s the kind of irony that makes you pause—the man crafting divine visions was fighting his own earthly battles.

He was also intensely religious, almost to a fault. He would obsess over the spiritual vibe of his work, repainting a saint’s face if it didn’t feel holy enough. He once even turned down a commission because the project didn’t feel sacred enough.

His Archangel Michael Defeating Satan (1635) is peak Reni: Michael’s face is so serene that it’s practically otherworldly, crushing evil with an almost eerie calm.

But this piety came with a side of drama.

Reni was notorious for being moody, ditching projects if the vibe was off. One story claims he walked out on a Vatican gig because he didn’t like the room’s energy.

That’s not just artistic temperament—that’s diva-level confidence.

Cultural Canvas is a reader-supported publication. Every like, comment, share, or donation helps us grow—your support truly matters!

Parallels, Divergences, and Lasting Influence

Reni and Caravaggio were two sides of the Baroque coin.

Both were shaped by the Counter-Reformation, when the Catholic Church leaned on art to win hearts and minds. They painted for the same crowd—popes, cardinals, nobles—who wanted images that hit hard. Both had a flair for theatricality, using bold poses and dynamic scenes to make you feel the story. And both were innovators, pushing painting into new territory.

Yet their methods diverged.

Caravaggio’s realism was grounded in the streets, his models were flawed, human, and real. Reni idealized everything, giving his figures a polished, almost divine glow.

Caravaggio’s light was like a spotlight in a noir film.

Reni’s was like dawn breaking through clouds.

Caravaggio lived chaotically, fleeing Rome after a murder charge and dying mysteriously in 1610. Reni, while not exactly stable, kept it together enough to build a career, even if he was dodging debt collectors.

His Final Years

By the 1620s, Reni had returned to Bologna, a celebrated master whose reputation extended across Europe. Caravaggio was gone, but his influence endured, shaping generations of painters.

Reni, too, continued to refine his craft, producing works such as St. Matthew and the Angel (1640), a composition that exemplifies his mastery of ethereal light and idealized form, reaffirming his place among the greats.

But his later years were rough.

His health tanked, his gambling debts piled up, and he got more reclusive, haunted by his own perfectionism. When he died in 1642, he left a legacy that’s too often eclipsed by Caravaggio’s drama-king status.

Yet Reni’s vision, his celestial compositions, and his graceful figures formed a foundation that echoed through Rococo, Neoclassicism, and beyond.

Guido Reni wasn’t just Caravaggio’s rival, he was his equal, his opposite, and maybe his secret muse.

Their feud was less about punches and more about pushing each other to be better.

Caravaggio gave us the raw, Reni gave us the radiant, and together they defined the Baroque. Behind Reni’s glowing canvases was a man who gambled hard, believed harder, and had the guts to walk away from the Vatican if the mood wasn’t right.

Picture one of his angels or Caravaggio’s gritty saints, imagine them sizing each other up across a Roman piazza, brushes ready, egos blazing.

That’s not just rivalry—it’s the essence of art itself.

Missed our last story? Read it here ↓

And I've just posted about yet another infamous rivalry of the Baroque era: Bernini and Borromini.

What an awesome read. And I was just reading about them for my exams in History of Art. 😅😭