Jean-Léon Gérôme

Master of Exoticism, Controversy, and Technical Brilliance

Jean-Léon Gérôme was a French painter and sculptor whose work defined 19th-century academic art. Known for his hyper-detailed Orientalist scenes, historical epics, and genre paintings, he was a titan of the Salon. But his legacy is a battleground—adored, reviled, and endlessly debated.

Never miss a post! Subscribe for free.

Born on May 11, 1824, in Vesoul, France, Gérôme trained under Paul Delaroche, mastering a meticulous, almost photographic style.

His early work, like The Cock Fight (1846), won him praise for its youthful energy and classical polish.

The Allure and Controversy of Orientalism

Gérôme’s Orientalist paintings, like The Snake Charmer (1879), are among his most iconic and contentious.

He traveled to Egypt and the Middle East, sketching bazaars, harems, and deserts. His works captivated Western audiences with their vivid detail and immersive realism.

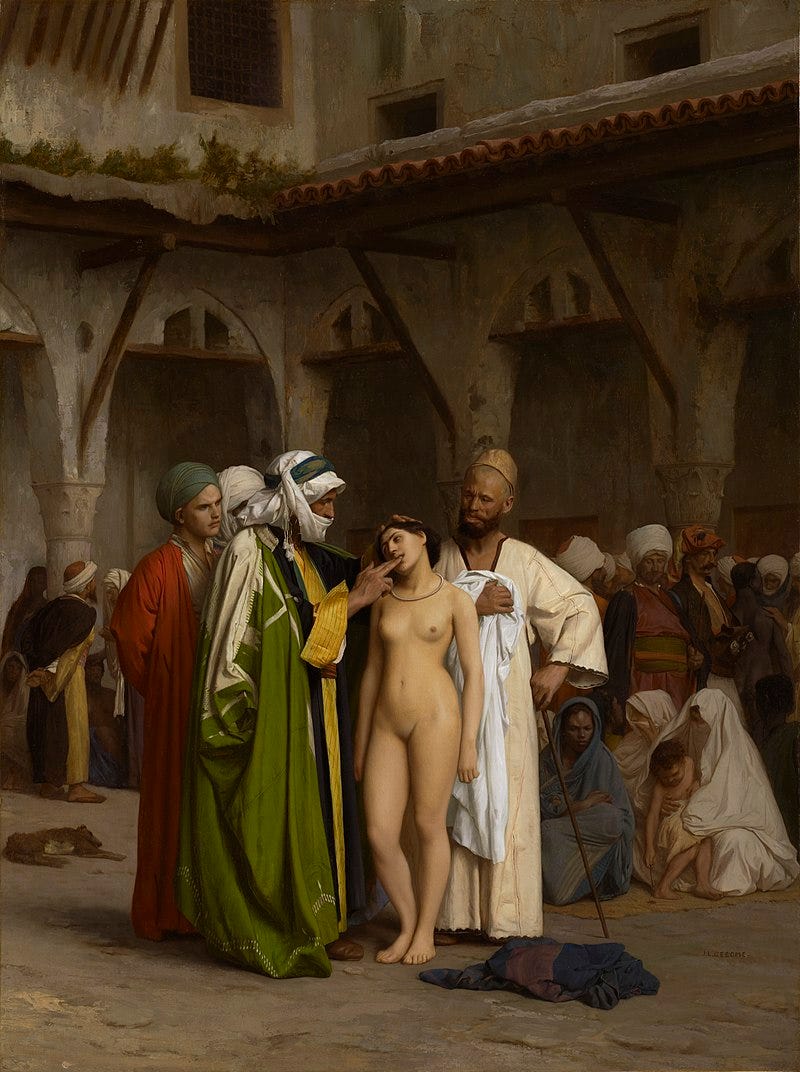

Unlike many Orientalist painters who relied on imagination, Gérôme based his scenes on direct observation. The Slave Market (1866), for example, depicts a Middle Eastern or North African setting where a man inspects the teeth of a nude Abyssinian slave, a practice documented in Cairo’s slave markets at the time.

While historically accurate, Gérôme’s framing of these scenes often emphasized submission and sensuality, reinforcing Western fantasies about the ‘exotic’ East.

Yet, Gérôme wasn’t just an Orientalist. His historical paintings, like Pollice Verso (1872), brought ancient Rome to life with gladiatorial grit.

That iconic thumbs-down gesture? He didn’t invent it, but his painting popularized the idea in modern culture.

The true meaning of pollice verso in ancient Rome is debated—was it thumbs up, down, or tucked in?

Gérôme’s research was obsessive, his accuracy unmatched, but his artistic choices shaped perceptions rather than confirmed historical fact.

His technical skill was astonishing. His surfaces gleam with precision. Every fold of fabric, every glint of metal is rendered with surgical care. Critics called him a “painter of glass” for his slick finishes. But some, like Émile Zola, sneered, saying his work lacked soul—too much polish, not enough depth.

Gérôme was a staunch defender of academic tradition and loathed the Impressionists.

He called their work sloppy and degenerate, clashing with the avant-garde. As a professor at the École des Beaux-Arts, he trained hundreds, but his rigidity alienated progressive artists.

Cultural Canvas is a reader-supported publication. Every like, comment, share, or donation helps us grow—your support truly matters!

A Life of Exotic Creatures and Sculpted Realism

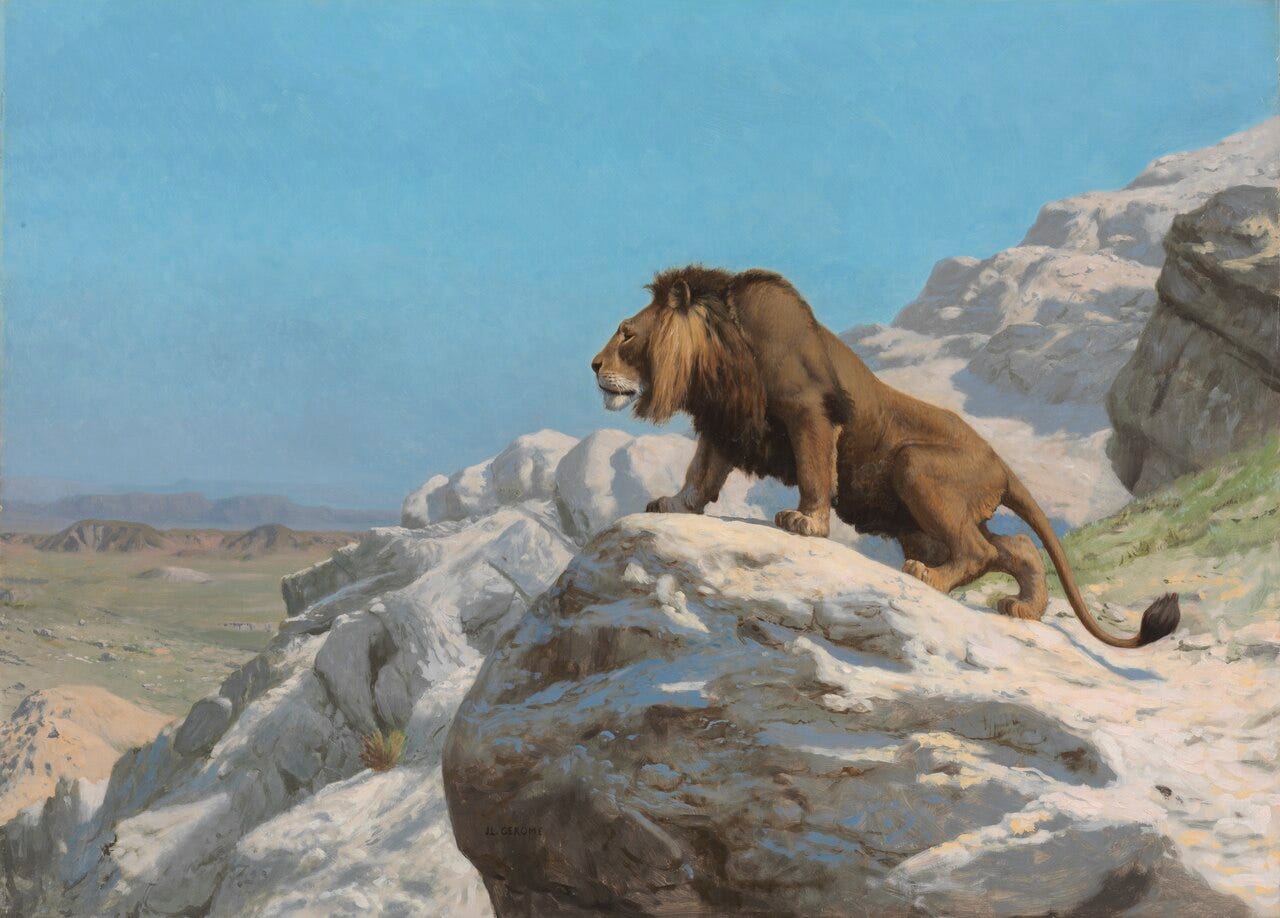

His personal life was less dramatic but not without intrigue. He married Marie Goupil, daughter of a powerful art dealer, securing wealth and connections. Their home was a menagerie—lions, tigers, and monkeys roamed his studio, inspiring works like The Lion on the Watch (1885).

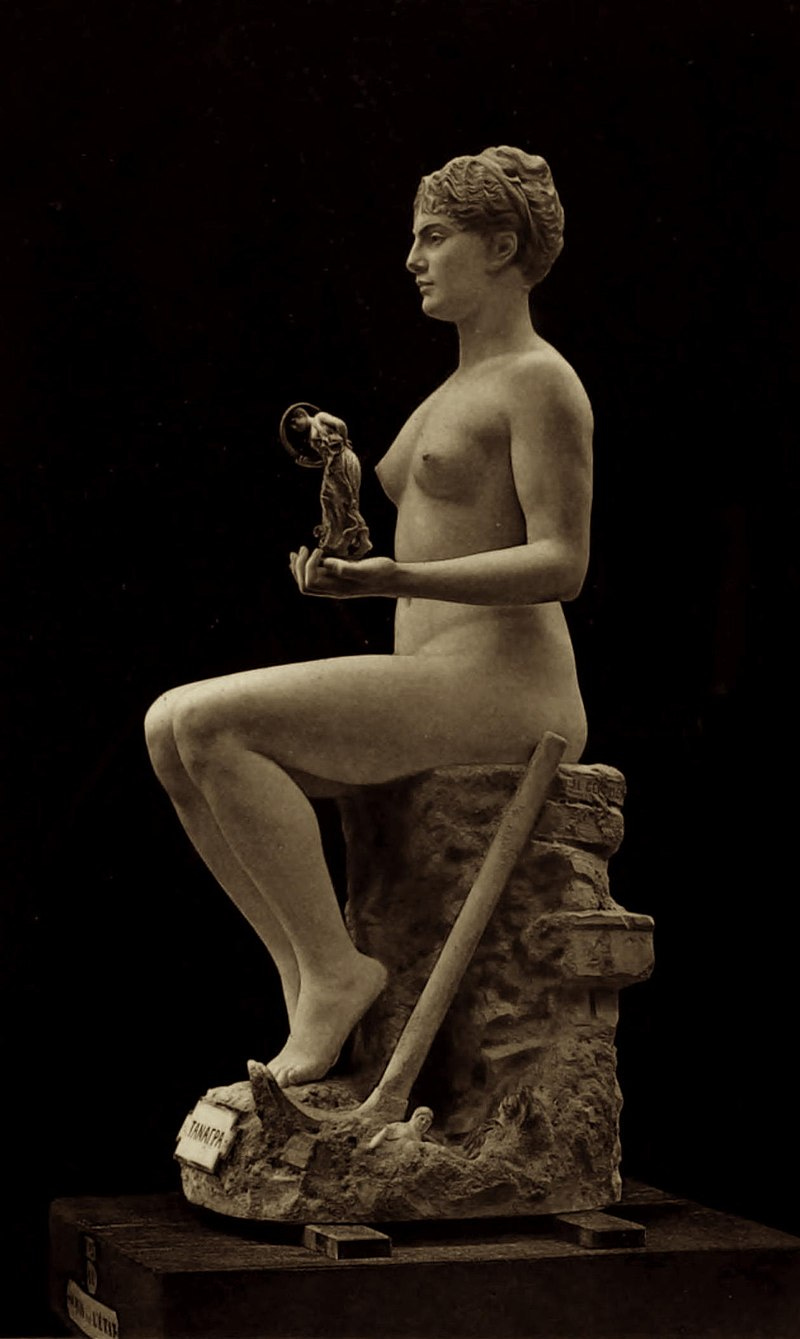

Later in life, Gérôme turned to sculpture, creating works like Tanagra (1890), a delicate figure holding a hoop. He even painted his bronzes for hyper-realism.

Critics were split—some saw genius, others gimmickry.

The Dark Side of Obsession

Gérôme’s obsession with authenticity had a troubling side. He collected ethnographic artifacts, weapons, textiles, and even human skulls for accuracy. This magpie approach fed his art but reflected the era’s colonial plunder.

His studio was a microcosm of empire, stuffed with looted treasures.

A Legacy in Decline

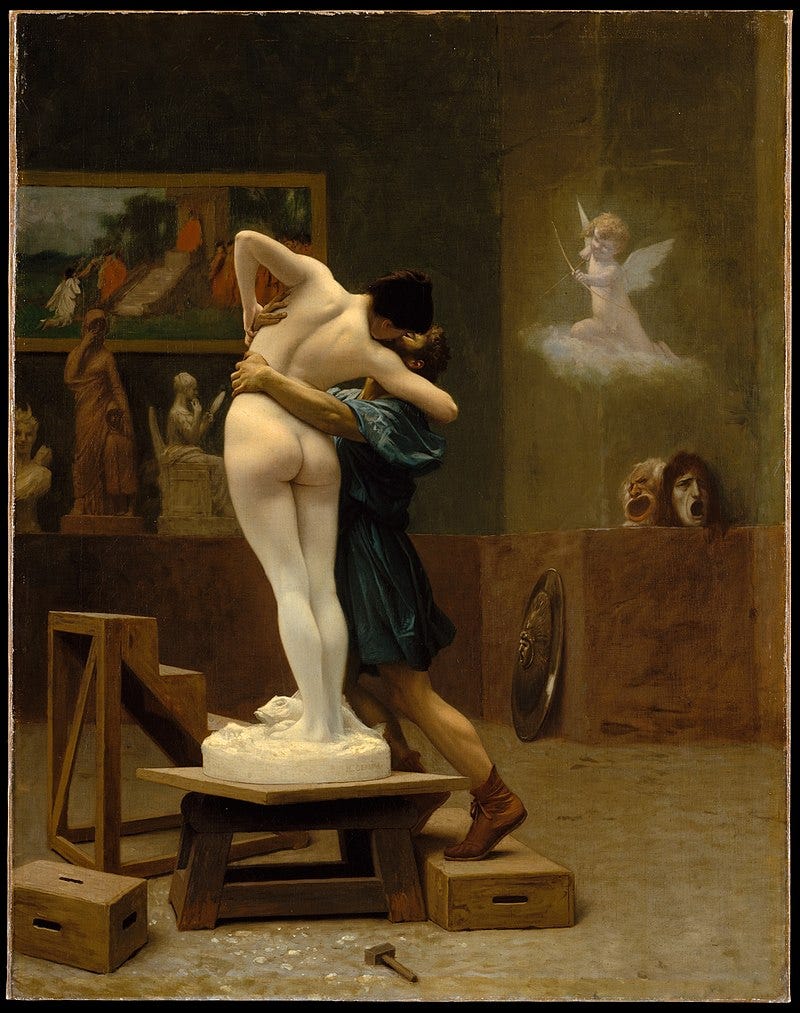

By the 1880s, Gérôme’s star waned. Impressionism and modernism eclipsed academic art. He doubled down, painting mythological scenes like Pygmalion and Galatea (1890), but critics called him outdated.

His bitterness grew—he died feeling forgotten, his style mocked.

Gérôme’s work can feel cold, his perfectionism stifling. His resistance to change made him a relic in his own time, clinging to a fading ideal of art as craft over expression.

He wasn’t above pandering. His eroticized nudes, like Phryne Before the Areopagus (1861), catered to wealthy patrons’ tastes.

He cloaked titillation in classical guise, dodging censorship while feeding the male gaze.

Gérôme Still Matters

Today, Gérôme’s legacy is polarized. Museums like the Getty and Orsay celebrate his virtuosity, but scholars critique his complicity in colonial fantasies. His paintings fetched millions, yet they’re often absent from modernist narratives, dismissed as relics of a stuffy era.

Gérôme is a paradox—brilliant and flawed, a master craftsman whose vision was both expansive and blinkered.

His work forces us to grapple with art’s power to enchant and deceive.

Look at his paintings, marvel, but don’t look away from the shadows they cast.

Thank you for being part of Cultural Canvas! If you love what we do, consider supporting us to keep it free for everyone. Stay inspired, and see you in the next post!

without shadow, no light

Criticizing someone from the past based on modern sensibilities is a cheap trick of shallow thinkers.