Hello, Dear Reader

We’ve all heard the term Impressionism, but what does it truly mean, and how did it come to be? Today’s story is about just that: a single painting, a biting critique, and a vision that launched a movement.

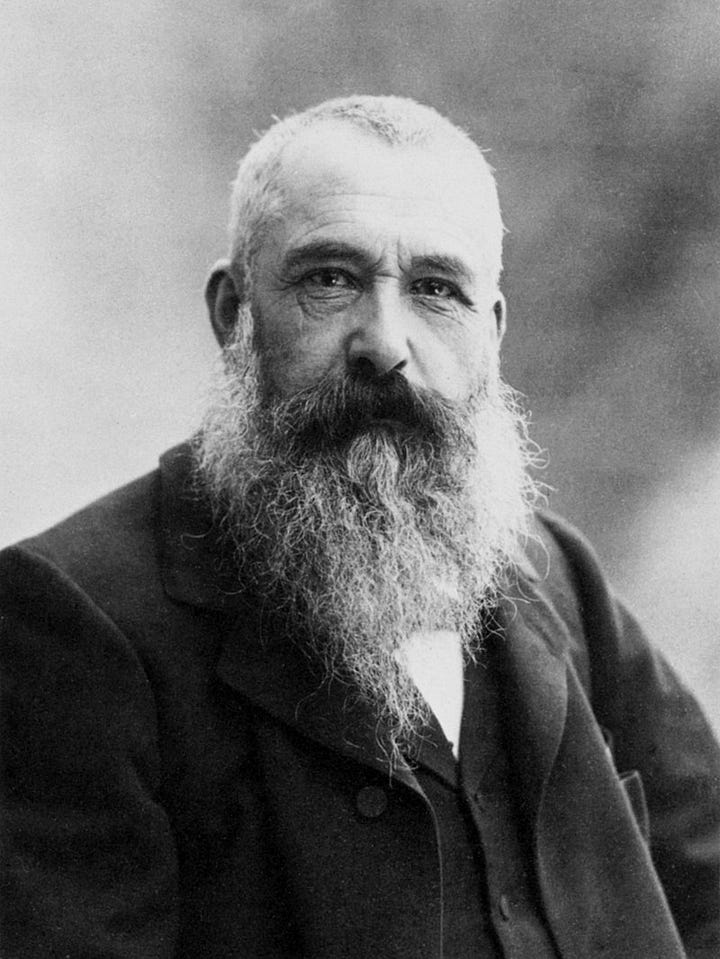

In 1874, a group of defiant Parisian artists broke ranks with tradition, staging an exhibition that would shake the art world. Frustrated by the rigid, formulaic tastes of the official Paris Salon (the gatekeeper of artistic legitimacy), they mounted their own show. Among them was Claude Monet.

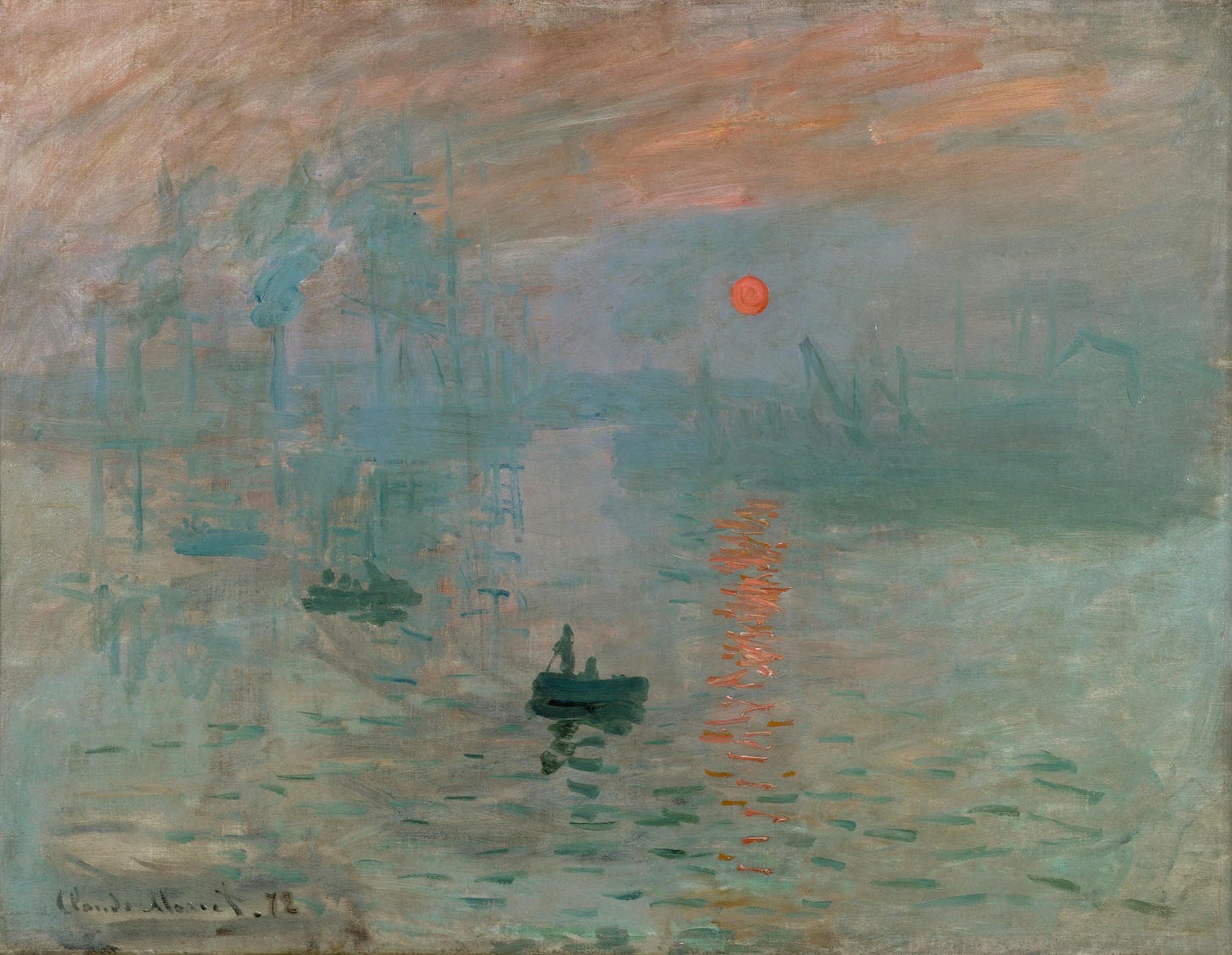

His canvas, Impression, Sunrise (Impression, soleil levant), a hazy, vibrant depiction of Le Havre’s harbor at dawn, would not only shock viewers but unwittingly christen one of the most influential art movements in history: Impressionism.

This is the story of how one painting, dismissed as

“wallpaper in its embryonic state”—sparked a revolution in art.

A Rebellious Exhibition

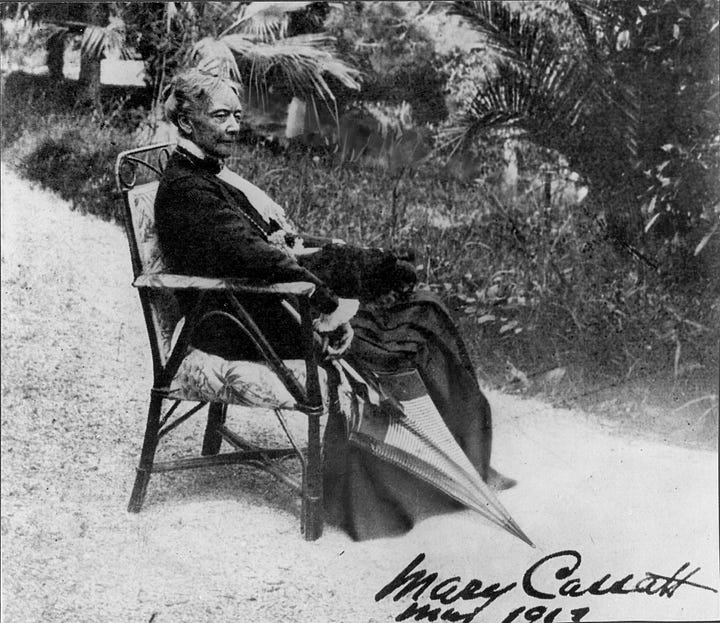

The Paris Salon, held annually, was the pinnacle of artistic prestige in 19th-century France. Its juries favored polished, academic works like grand historical scenes, mythological dramas, and meticulously detailed portraits. But for a group of young artists, including Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Mary Cassatt, and Edgar Degas, the Salon’s conservatism felt like a straitjacket.

Their works—bold, vibrant, and unpolished—were routinely rejected.

So, in 1874, they took a daring step. Calling themselves the “Société Anonyme des Artistes,” they rented a studio on the Boulevard des Capucines and mounted their own show. It was a declaration that art could thrive outside the Salon’s gilded walls.

Over 3,500 visitors came, curious to see what these rebels had to offer. Among the 165 works on display was Monet’s Impression, Sunrise.

A Hazy Harbor, a Radical Vision

At first glance, Impression, Sunrise is deceptively simple. A glowing orange sun rises over the harbor of Le Havre, its reflection shimmering on the water. Boats and cranes emerge from a misty haze, their forms blurred by loose, rapid brushstrokes capturing not a frozen moment but the fleeting sensation of dawn.

To modern eyes, it’s beautiful, evocative, even serene. But to many in 1874, it was baffling, even offensive. The painting’s sketch-like quality, its lack of crisp detail, flew in the face of academic standards.

Where was the precision? The grandeur? To some, it looked like Monet hadn’t bothered to finish it.

Monet wasn’t trying to replicate reality like a photograph. Instead, he sought to capture what he called ‘the effect’—the transient play of light and atmosphere. This was art as sensation, not documentation.

The Critic’s Jab That Named a Movement

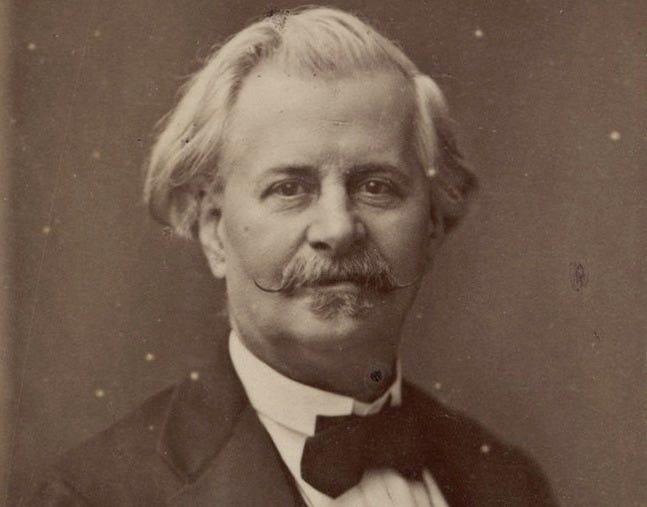

Louis Leroy, sent to review the show for the satirical Le Charivari, didn’t just pan Monet—he accidentally named a movement. In his scathing, tongue-in-cheek review, he wrote:

“Impression—I was certain of it. I was just telling myself that, since I was impressed, there had to be some impression in it… Wallpaper in its embryonic state is more finished than that seascape.”

Leroy’s review was meant to mock. He seized on the word impression from Monet’s title, using it to deride the entire group as sloppy amateurs who produced half-finished sketches. He dubbed them Impressionists, a term dripping with sarcasm.

But Leroy’s jab backfired spectacularly.

Far from being insulted, Monet and his peers embraced the label. They saw it as a fitting description of their mission: to capture the fleeting, subjective impressions of the world around them.

By 1876, the group was proudly calling themselves Impressionists, and their third exhibition was officially titled the “Impressionist Exhibition.”

What began as ridicule became a badge of honor.

Cultural Canvas is a reader-supported publication. Every like, comment, share, and donation helps us grow—your support truly matters!

The Birth of Impressionism

Impression, Sunrise with its loose brushwork, vibrant colors, and focus on everyday life, heralded a new way of seeing.

The Impressionists rejected the Salon’s obsession with historical and mythological subjects. Instead, they painted the world as it was: bustling cities, quiet landscapes, moments of ordinary beauty.

Their approach was radical not just in style but in philosophy. They worked en plein air (outdoors), capturing the changing light and weather in real time. They used bright, unmixed colors to convey vibrancy and movement. And they embraced imperfection, letting visible brushstrokes reveal the artist’s hand.

This was art that celebrated spontaneity over polish, feeling over formula.

The public was initially skeptical, even hostile. But over time, the Impressionists won hearts. Their paintings spoke to a modernizing world and by the 1880s, Impressionism had gained a foothold.

A Lasting Impression

Today, Impression, Sunrise hangs in the Musée Marmottan Monet in Paris, a quiet testament to its impact.

It’s hard to overstate how much it changed art.

Impressionism paved the way for countless modern movements like Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, Expressionism, that prioritized emotion and experimentation over rigid realism.

Monet himself would go on to create some of the most beloved works in history, from his water lilies to his haystacks. But Impression, Sunrise remains his defining moment, the spark that ignited a revolution.

Louis Leroy thought he was burying Monet with his sarcasm. Instead, he handed him a legacy.

The next time you see a painting that captures a fleeting moment, a sunrise, a garden, a glimmer of light, remember the “embryonic wallpaper” that started it all.

Missed our last story? Read it here↓

Don’t miss the newest episodes of our podcast!

Thank you for being part of Cultural Canvas! If you love what we do, consider supporting us to keep it free for everyone. Stay inspired and see you in the next post!

Thank you for sharing 🙏

The definition of beauty has taken a few turns along the way, hasn’t it? When we think back now to the academic process of rendering what is seen being judged for its exactitude seems almost preposterous. Yet we have to put our head into a world pre photography, when the talent to represent what the eye beholds lay only in the brush stokes of the artist.

It was as dramatic as going back to the invention of fire, and how light first shone in the darkness so we could see anything in the night at all… how precious fire must have been for ages is how precious representing reality was for ages as well.

To let go of representation at this stage meant to paint what was actually being seen in all its misty haze and irresolute line. Monet’s gift of seeing what light did and how it actually refracted in air was actually closer to painting reality than what the realists were doing. Imagine that?!