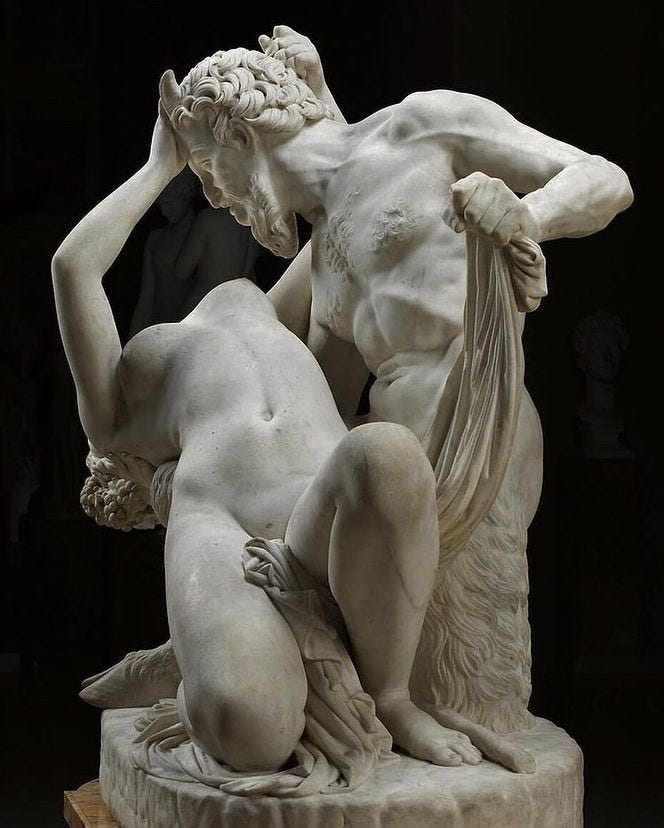

Back in the early 1830s, Pradier was already a big name in French sculpture. Prix de Rome winner, contributor to the Arc de Triomphe, he was moving in high Parisian circles. He had the neoclassical polish down perfectly with flawless anatomy and elegant forms.

But he was getting restless with how restrained and idealized everything felt.

He wanted something more alive, more raw.

So he took on this ancient theme and turned it into something intensely physical. He started with a plaster model around 1830, then spent four years carving it in marble. He wanted to push the boundary between antiquity and sensuality.

When it debuted at the Salon of 1834, people lost it. The technical skill, the smooth marble, the way the flesh seemed soft and veined was undeniable, but the overt eroticism was too much for many.

Critics called it scandalous, too realistic, too explicit. Rumors flew that the bacchante was modeled after Pradier’s mistress Juliette Drouet (who later became Victor Hugo’s lover), and maybe even the satyr echoed the sculptor himself.

The piece was considered too sensual, too explicit in its physicality, too close to the edge. So much so that the French state, which often purchased major Salon works, refused to buy it.

Instead, a wealthy Russian collector, Count Anatole Demidoff, took it and shipped it off to his villa in Florence, where it stayed for decades.

And over time, the outrage died down. By the late 19th century, it was seen as one of Pradier’s finest works, a brilliant bridge between neoclassicism and the more passionate Romantic spirit.

It eventually returned to France and entered the Louvre’s collection in 1980, where it now stands in the Richelieu wing, room 225.

The original plaster model is in the Palais des Beaux-Arts de Lille.

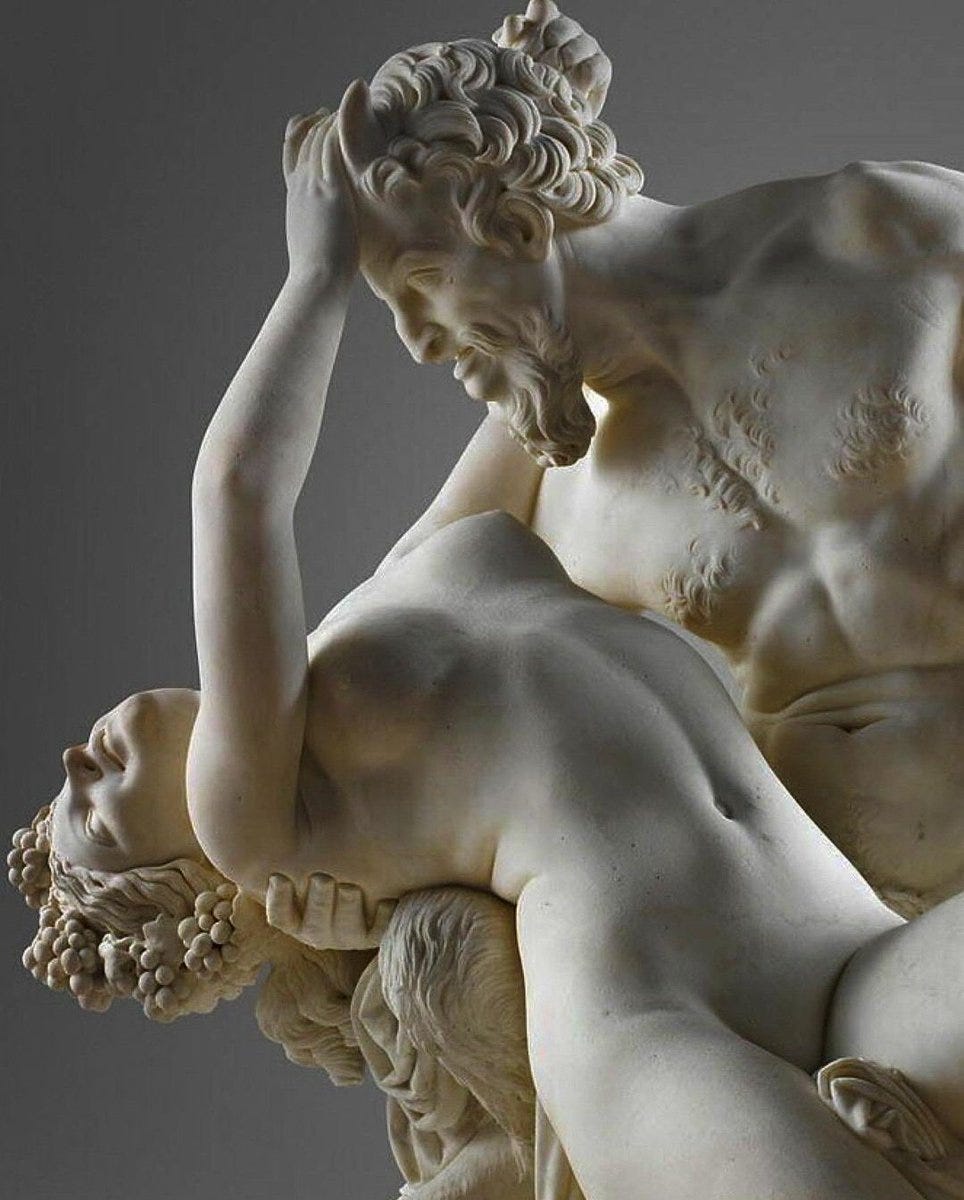

Here is a detail of this striking marble group. Notice the tension in the bodies, the way the light plays across the skin-like polish, and that electric closeness between the figures.

Today it doesn’t shock quite as it did in 1834, but you can still feel the mythic heat, the wildness of Dionysian revelry captured in cold, perfect marble.

Pradier really did make the stone breathe.

Thank you for being part of Cultural Canvas! If you love what we do, consider supporting us.

Stay inspired and see you in the next post!

Stunningly, sensuously beautiful. To translate the vibrancy of living flesh into stone shows the absolute mastery of his art.

Needs to have a pressure sensitive mat around it, which plays Frank Zappa's Dirty Love ❤ on contact