Rembrandt van Rijn

The Light of Dutch Golden Age

In a time when Amsterdam’s canals brimmed with commerce and creativity, one artist wielded light and shadow to capture the very essence of humanity.

Rembrandt van Rijn was a master of emotion.

With over 300 paintings, 300 etchings, and countless drawings, his work remains a testament to the power of art to transcend time.

From Leiden to Luminary

Born on July 15, 1606, in Leiden, Rembrandt was the ninth child of a miller and a baker’s daughter. Though not wealthy, his family sent him to Latin school, steeping him in the classics before he briefly attended Leiden University.

By 14, he was apprenticing with local painter Jacob van Swanenburg, and later with Pieter Lastman in Amsterdam, where he learned to infuse biblical and historical scenes with drama.

By his mid-20s, he was back in Leiden, running a studio with Jan Lievens, his bold use of chiaroscuro already setting him apart.

Leiden’s intellectual ferment shaped Rembrandt’s vision. His early masterpiece, The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp (1632), captures this blend of curiosity and humanity. The painting, a group portrait of a public dissection, balances clinical precision with the onlookers’ vivid expressions of awe.

A Golden Age Master

By 1631, Rembrandt had settled in Amsterdam, marrying Saskia van Uylenburgh in 1634. Her connections to the art world and his own talent made him a darling of the elite. His studio buzzed with students, his commissions multiplied and works like Belshazzar’s Feast (c.1635) stunned.

Full story here

Lesser known is Rembrandt’s passion for collecting.

His home was overflowed with treasures—shells, armor, exotic fabrics, even a bust of Homer.

His etchings, like the Hundred Guilder Print (c.1648), showcase his skill as a printmaker. These prints spread his fame, turning Rembrandt into a name far beyond Amsterdam.

Cultural Canvas is a reader-supported publication. Every like, comment, share, and donation helps us grow—your support truly matters!

Shadows and Resilience

Yet Rembrandt’s life was no unbroken ascent. The death of Saskia in 1642, shortly after their son Titus’s birth, left him reeling. His monumental The Night Watch (1642), with its dynamic militia company and glowing girl in gold, redefined group portraiture but may have sparked tensions with patrons.

His relationship with Hendrickje Stoffels, his housekeeper-turned-partner, and later Geertje Dircx, caused scandals, as did his reckless spending.

By the 1650s, bankruptcy forced him to auction his cherished collection and move to a modest home.

Adversity only deepened his art.

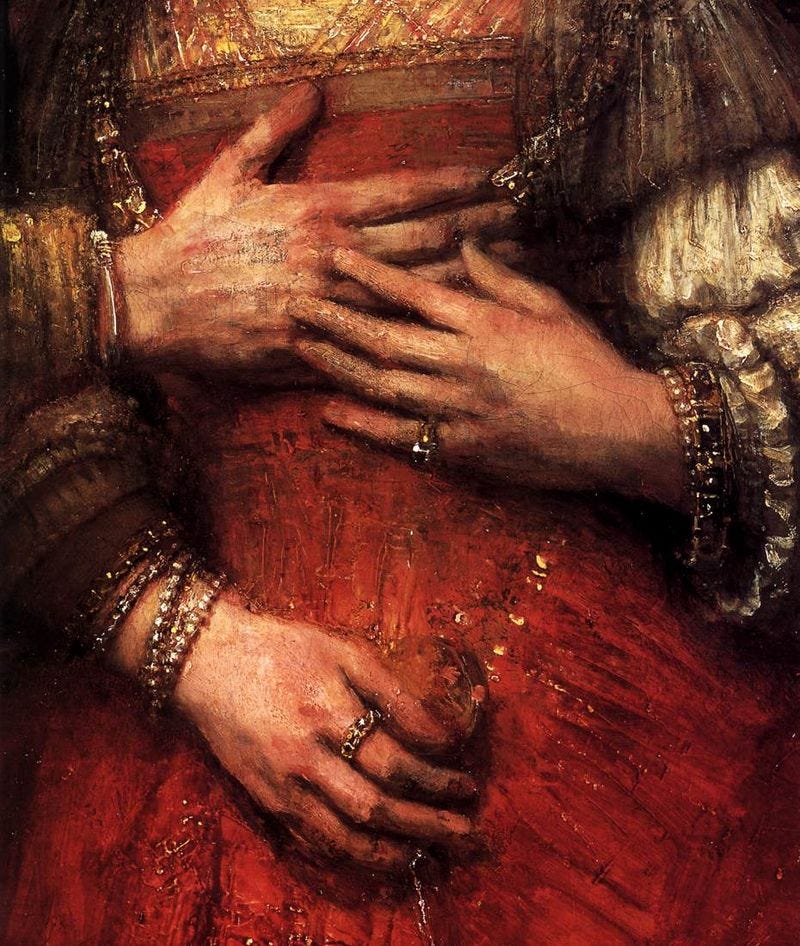

The Jewish Bride (c.1665–69) radiates love through the couple’s gentle touch and rich textures.

Bathsheba at Her Bath (1654) portrays a woman torn by duty and desire, her nude form bathed in soft light, her contemplative gaze achingly human.

Similarly, Danaë (1636) captures a mythological figure awaiting Zeus.

Hidden Treasures

While The Night Watch and The Return of the Prodigal Son (c. 1668)—a tender meditation on forgiveness—dominate his legacy, lesser-known works reveal Rembrandt’s versatility.

The Blinding of Samson (1636) is visceral, its brutal biblical scene amplified, Samson’s agony is raw and unforgettable.

His Storm on the Sea of Galilee (1633), his only seascape, captures divine calm amid chaos. Its theft in 1990 leaves a haunting absence—but we can only hope it still graces someone’s wall, feeding their ego, and hasn’t been destroyed.

His etchings, like the playful Self-Portrait with Saskia (1636), offer glimpses of his personal joy.

Rembrandt’s The Syndics of the Drapers’ Guild (1662) transforms a corporate commission into a lively study of character, each man’s gaze distinct and engaging.

These works, often overshadowed, show an artist who could find profundity in the mundane.

The Heart of Rembrandt

What makes Rembrandt endure is his empathy. His figures seem to live and breathe.

Even in ruin, he painted on.

His late works like The Return of the Prodigal Son radiate compassion. The father’s embrace, the son’s surrender, bathed in warm light, speak to universal longing.

Lesser known is his resilience. Even in grief and ruin, Rembrandt never stopped creating—and never stopped feeling: love, loss, hope.

Thank you for being part of Cultural Canvas! If you love what we do, consider supporting us to keep it free for everyone. Stay inspired and see you in the next post!

👏👏👏