⚠️ A Note Before You Scroll

This article leans into the mood of the season—unsettling, uncanny, and steeped in historical strangeness. If you’re sensitive to anatomical imagery or prone to unease, viewer discretion is advised. What follows is not horror fiction. It’s real. And it’s still in jars.

On the banks of the Neva River, in a pale turquoise Baroque building crowned with a spinning golden sphere, sits one of the strangest museums I've ever been to.

This is the Kunstkamera in St. Petersburg — Russia’s first public museum, founded in 1714 by Peter the Great, a tsar obsessed with proving that monsters were not made by witches, but by nature.

His logic? If you could bottle the grotesque, you could neutralize the fear.

So he did.

He ordered his empire to send him the unusual, the malformed, the unexplainable.

And they did.

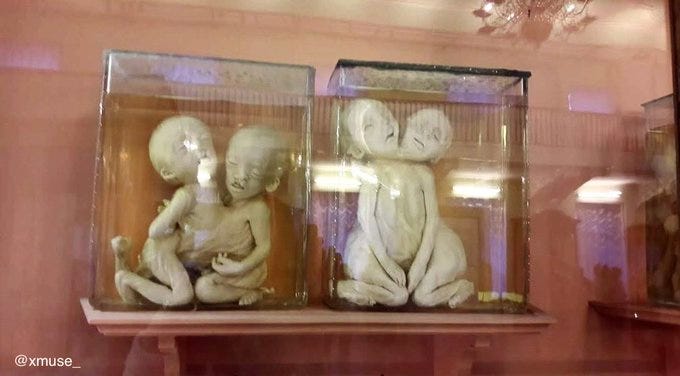

The result still haunts the second floor: a long, silent room lined with 300-year-old glass jars, each holding a preserved fetus—some with two heads, some with one eye, some with limbs that never learned where to stop.

They are not gory. They are clinical. But they are also deeply human, and deeply unsettling. The display hasn’t changed much since the 1700s. Neither has my discomfort since the first visit.

Peter wasn’t just collecting anomalies. He was staging a confrontation. Against superstition. Against shame. Against the idea that deformity was divine punishment. In his world, to pickle a body was to disarm a myth. And in a way, it worked. But it also left behind a museum where fear was bottled, labeled, and put on display.

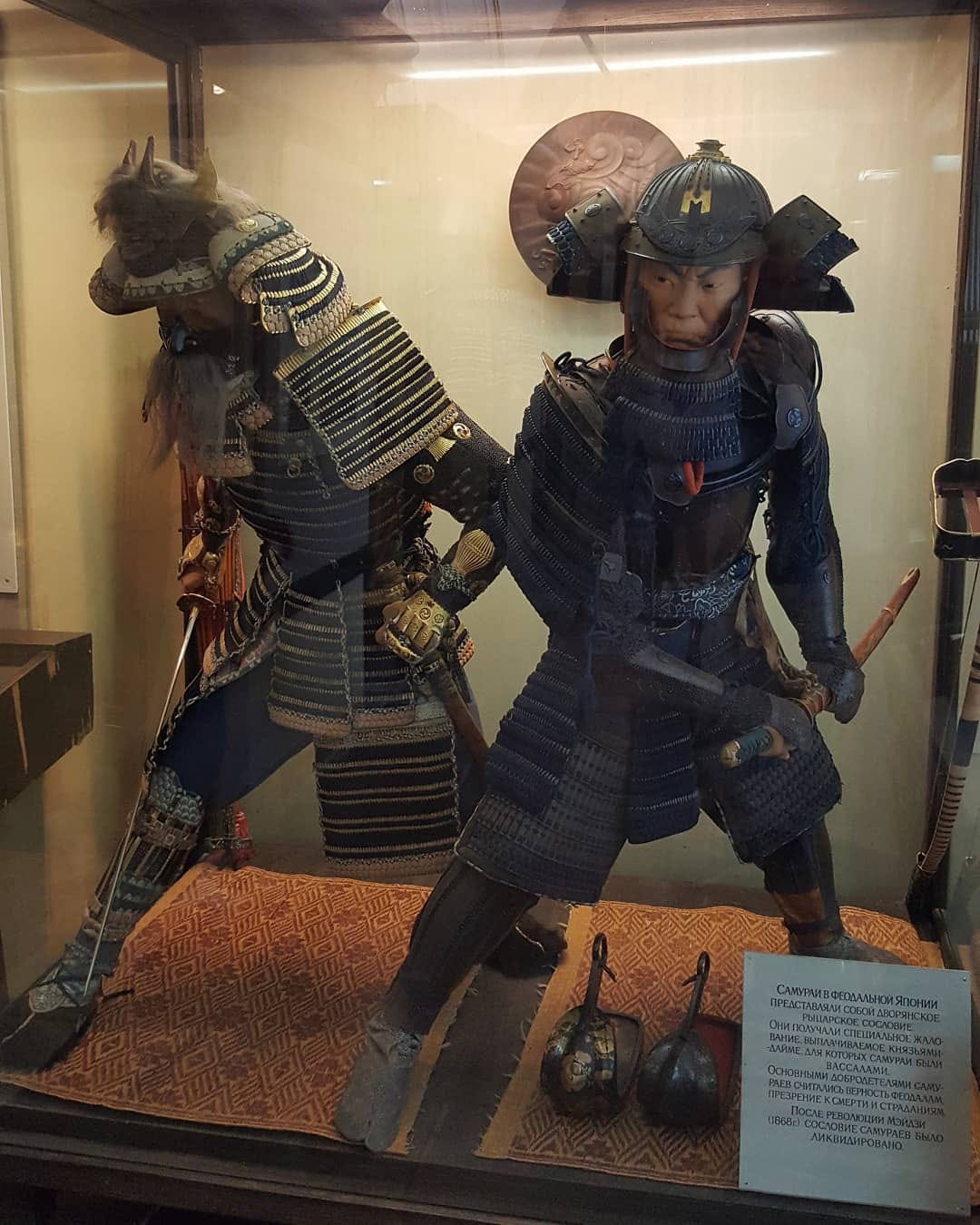

Downstairs, the tone shifts. Here, the empire’s gaze turns outward. Peter sent explorers across the globe to gather proof that the world was vast, varied, and, most importantly, not Russian.

The result is a colonial scrapbook in glass: a seal-skin Inuit kayak, a child-sized Japanese samurai helmet, a wooden mask from Papua New Guinea bristling with pig tusks, a Siberian shaman’s drum lined with reindeer fur. Tools, weapons, clothes—each tagged, boxed, and displayed like trophies from a planetary scavenger hunt.

The building itself is Baroque, but not the Versailles kind. Think creaky wooden floors, high ceilings, and a quiet that feels older than the city around it.

The Kunstkamera Museum needs to be seen to be believed.

Go in the morning. In autumn or in winter when the city is grey and the river is frozen and the museum feels like it’s holding its breath. Two hours is enough to see the main rooms, unless you get stuck staring into the eyes of a child who never blinked.

Even now, as I write this, I feel that same heavy, unsettling pull I did years ago—breathing in the oddity of that place, and the quiet weight of what it holds.

If the preserved specimens are too much, skip the second floor. But know this: the Kunstkamera doesn’t just show you what Peter collected. It shows you what he feared. What he wanted to control. What he tried to explain away.

It’s a reliquary of empire, science, and spectacle. A place where the Enlightenment pickled its shadows and put them on display.

Strange, yes. Educational, absolutely.

But also a mirror—one that reflects how far we’ve come, and how much we still flinch when faced with the unfiltered truth of the body.

If you’re in St. Petersburg, go. Not for the pictures. For the reckoning.

Thank you for being part of Cultural Canvas! If you love what we do, consider supporting us to keep it free for everyone. Stay inspired and see you in the next post!

Sounds like Peter believed in the saying “to defeat your fears, one must confront them” (something to that effect) to the point of macabre behavior…

Sounds like an intriguing and interesting place to visit, knowing that you must be prepared for it. Thanks for sharing Muse!

Peter's journey through Europe, where he learned some shipbuilding trades, amongst others, showed him how far Russia was behind. When one lives in a country so large, it is easy to get used to how things are and not realize how one matches up to the rest of the world. The museum seems to have done the trick and for those who go still does.