Imagine a city built on water, where every bridge is a threshold between secrets, revelations, and pleasures half-spoken. Venice in the late 17th century was such a place—a labyrinth of marble palaces and shadowed alleys, a kingdom of intrigue.

It was here, amid the feverish whirl of Carnival, that the moretta mask emerged as a singular emblem of feminine mystery. Not the boisterous bauta with its jutting chin and gilded excess, nor the grotesque leer of the plague doctor, but something far more intimate: an oval of black velvet, soft as a lover's glove, that clung to the lower face like a secret too delicate to utter.

This was an instrument of seduction, enforced by silence, that turned the act of looking into an art form all its own.

Cultural Canvas is a reader-supported publication. Every like, comment, share, and donation helps us grow—your support truly matters!

The Moretta: Silence as Seduction

To understand the moretta, one must first grasp the peculiar alchemy of Venetian Carnival, that grand inversion of social order which stretched from Christmas to Shrove Tuesday, a pre-Lenten binge of hedonism sanctioned by the Church itself.

In a republic notorious for its rigid hierarchies—patricians lording over merchants, courtesans over nuns—masks dissolved the barriers of class and gender, if only for a season.

The word carnevale derives from the Latin carne vale, farewell to flesh, a ritual purging of earthly delights before the austerity of Lent. But in Venice, this farewell was anything but somber. It was a riot of gondolas ferrying masked revelers to illicit assignations, of gambling dens where fortunes flipped like cards, and of street theaters where commedia dell'arte troupes lampooned the powerful with acrobatic glee.

Masks, those papier-mâché marvels crafted by the guild of mascherari, were the great equalizers: a senator could rub shoulders with a fishmonger, a noblewoman with a streetwalker, all rendered anonymous under layers of feathers, gems, and gold leaf.

Carnival and Class Inversion

The moretta, however, stood apart in this masquerade of excess. Oval-shaped and strapless, it covered the wearer's face from forehead to chin, framing the eyes in wide, unblinking voids that invited scrutiny while denying reciprocity. Crafted from fine black velvet—moretta meaning little dark one—it was often veiled at the edges for added opacity, transforming the woman beneath into a figure of ethereal detachment.

But the true genius, or cruelty, lay in its fastening: a small ivory or wooden button protruding from the mask's interior, which the wearer was compelled to bite between her teeth.

To speak was impossible; the jaw locked in a perpetual, mute poise.

Thus also named servetta muta, the silent maidservant, it evoked the obedient handmaiden of classical theater, yet, wielded in the hands of patrician ladies, it became a weapon of exquisite power.

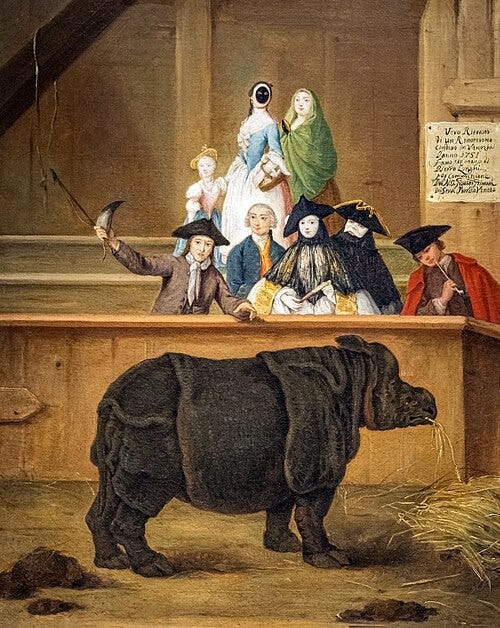

No wonder Pietro Longhi, that chronicler of Venetian domesticity, captured it in oils: in his 1751 painting The Rhinoceros, a woman pauses mid-gesture to adjust her moretta, her eyes locking with the viewer in a gaze that speaks volumes her mouth cannot.

The mask's origins are as enigmatic as its wearer.

Though it flourished in Venice during the 18th century, whispers trace it back to France, where mid-17th-century Parisian women adopted similar veils to shield their porcelain complexions from the sun—a practical vanity in an age when pale skin signified leisure, not labor.

These masques de velours crossed the Alps, evolving in the lagoon's humid embrace into something more ritualistic. By the 1680s, the moretta had taken root, not just for Carnival's bacchanalia but year-round: noblewomen donned it for convent visits, where gossip with cloistered nuns offered a sanctioned thrill, or for strolls along the liste—those fashionable promenades where assignations bloomed like water lilies.

Husbands reportedly encouraged its use; the enforced silence curbed their wives' tongues. One 18th-century chronicler, Giovanni Grevembroch, sketched it in his album of Carnival costumes, noting how it

"pleased the male counterpart," allowing men to steer conversations unchallenged.

From Power to Performance

Yet this masked a deeper subversion: in silencing the voice, the moretta amplified the body, turning every glance, every tilt of the head, into a cipher of desire. Consider the semiotics of such restraint. In an era when women's words were often policed—confined to salons or scripture—the moretta weaponized absence. The mouth, that portal of expression, was sealed; the eyes, windows to the soul, were left bare.

This asymmetry created what we might now call an "erotics of the gaze," a term borrowed from modern theorists but rooted in the Baroque's obsession with that jolt of wonder at the veiled divine.

The wearer became a sphinx: alluring in her opacity, her silence a canvas for the viewer's projections. Courtesans perfected the art; clad in tabarro cloaks of midnight silk, they glided through ridotti—the private gaming houses where fortunes and favors were traded—to ensnare admirers with a single, lingering look.

Giacomo Casanova alludes to such encounters in his Histoire De Ma Vie, describing masked women whose

"eyes alone betrayed a fire that words could only fan."

The moretta, then, was no mere accessory; it was a performance of power, inverting the male gaze by making it complicit in its own undoing.

To bite the button was to choose mystery over chatter, enigma over explanation.

Yet the moretta's muteness was not always liberating; it could curdle into isolation.

Biting down for hours strained the jaw, turning flirtation into endurance. And in Carnival's fever, where anonymity bred excess, the mask blurred lines perilously.

Venice's laws forbade masks outside designated seasons, yet enforcement was lax until 1797, when Napoleon's invasion shattered the Republic. The Treaty of Campo Formio ceded Venice to Austria, and with it, Carnival's license evaporated. Emperor Francis II banned masks outright, deeming them harbingers of moral decay. For nearly two centuries, the moretta languished in attics, a relic of a drowned world. It resurfaced fitfully in the 19th century's Romantic revival—Byron and Shelley donned disguises in Byronic defiance—but only in 1979, amid Italy's push to reclaim cultural heritage, did Carnival roar back to life.

The Digital Mask

Today, three million tourists flood the piazza each February, but the moretta remains rare, a shadow among the glittering bautas and colombinas.

Its silence feels anachronistic in our loquacious age of TikTok confessions and Instagram reels. What lingers, though, is the moretta's quiet indictment of our own performances.

In an era of filtered selves and algorithmic intimacy, we too craft masks—not of velvet, but of code and curation. The moretta reminds us that true allure often lies in what we withhold: the unspoken glance that says more than a soliloquy, the pause that invites pursuit.

Thank you for being part of Cultural Canvas! If you love what we do, consider supporting us to keep it free for everyone. Stay inspired and see you in the next post!

I wish I had had you for Western Civ at university. I would be so much better educated! I've never heard of the Moretta Mask, it's fascinating.

Seductive, but depending on silence. So she couldn't seduce by speaking, by showing her character, only her body.