The Painter Who Chased Paradise and Found Darkness

Paul Gauguin

Today, June 7, marks the birthday of Paul Gauguin (1848–1903), a man who abandoned the comforts of modern life to chase a vision of primal beauty, leaving behind a legacy as radiant as it is troubling.

His vivid canvases redefined art, but his life was a tangled mess of genius, rebellion, and moral downfall.

A Restless Beginning

Eugène Henri Paul Gauguin was born in Paris in 1848, but his early years were anything but ordinary. His father, a journalist, fled France with his family to Peru after Napoleon III’s coup in 1851, seeking safety in his wife’s homeland.

Gauguin’s childhood in Lima, surrounded by vibrant markets and Andean landscapes, planted seeds of exoticism that would bloom in his art decades later.

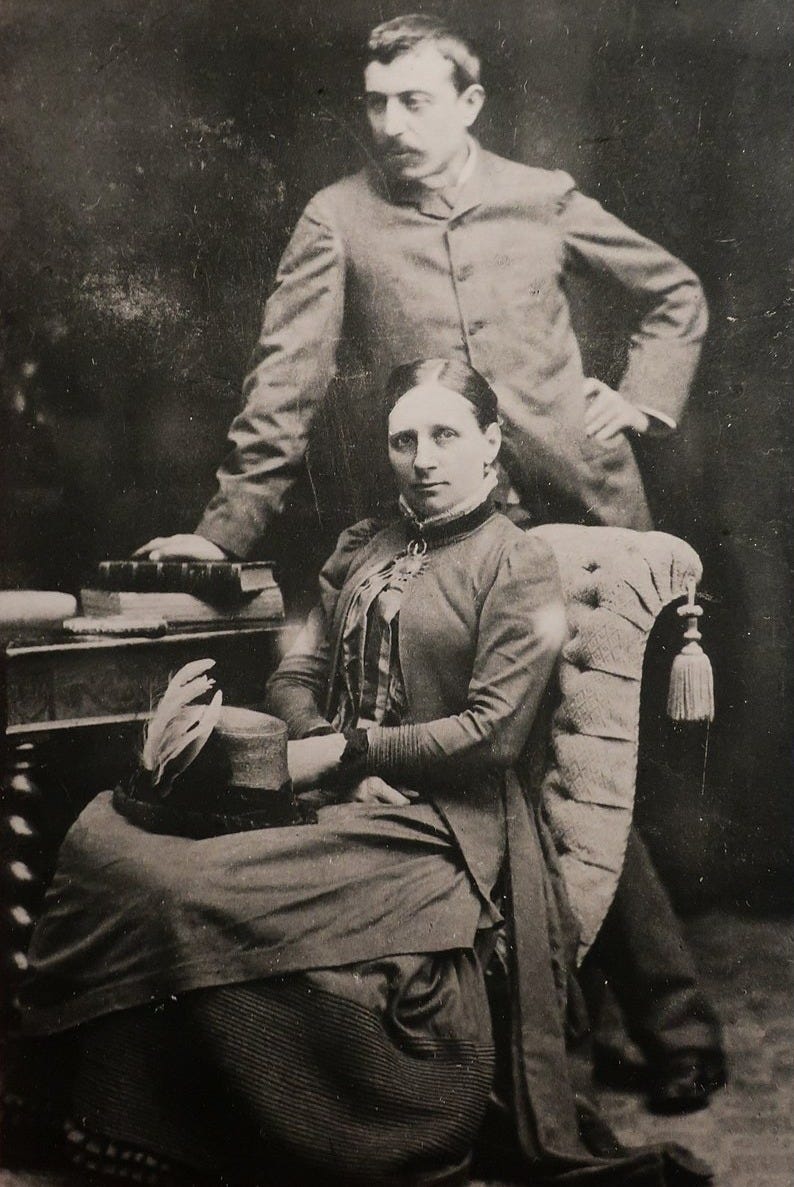

After his father’s sudden death, young Paul returned to France, raised in a world of bourgeois stability. By his twenties, he was a stockbroker, married to a Danish woman, Mette-Sophie Gad, with five children.

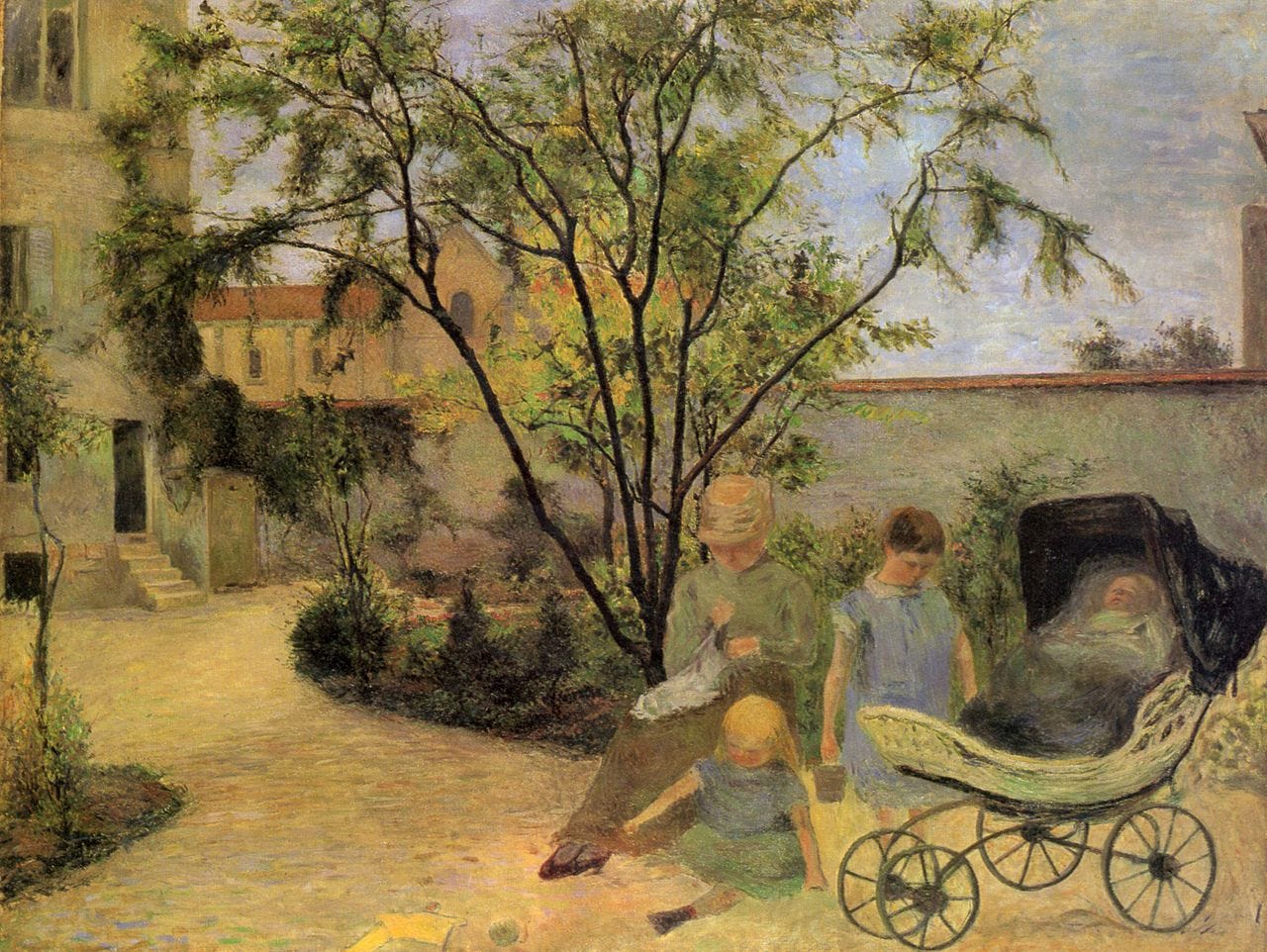

He painted on weekends, a hobbyist dabbling in Impressionism under the wing of Camille Pissarro. But beneath the surface of this respectable life, a restlessness churned.

The stock market crash of 1882 was the spark: Gauguin quit his job, declared himself a full-time artist, and plunged his family into poverty.

His wife, exasperated and rightly so, took their children to Copenhagen.

Gauguin followed briefly, only to return to Paris, alone, driven by a hunger for something greater than domesticity.

The Birth of a Visionary

In Paris, Gauguin’s art began to shift. He admired the Impressionists — Pissarro, Degas, Monet, but found their focus on fleeting light and urban life too dull.

He craved something deeper, more elemental.

In Brittany, he began forging a new style: bold outlines, flat colors, and symbolic depth. Paintings like Vision After the Sermon (1888) shocked the art world with their raw intensity, blending spirituality with a primal energy that felt almost ancient.

This was Gauguin’s break from Impressionism, a rebellion against its delicate brushstrokes. He called his approach Synthetism, aiming to distill emotion and meaning into simplified forms.

Beyond painting, Gauguin also experimented with sculpture, creating carved wooden and ceramic pieces influenced by Polynesian art and symbolism.

His rivalry with the Impressionists was philosophical. He saw their work as decorative, lacking the soul he sought. Yet he wasn’t without peers. At Pont-Aven, he clashed with younger artists like Émile Bernard, who claimed Gauguin stole his ideas for Synthetism. Their rivalry was less about hatred and more about egos colliding.

Gauguin often came out on top, but the tension fueled his drive.

The Van Gogh Episode

His most infamous rivalry was with Vincent van Gogh. In 1888, at the invitation of Theo van Gogh, Vincent’s brother and art dealer, Gauguin joined Vincent in Arles, southern France, to form an artists’ colony.

The idea was idyllic: two visionaries sharing a ‘Studio of the South’, painting side by side. Reality was messier.

Gauguin, confident and worldly, clashed with Vincent’s intense, fragile genius. They argued over everything—art, money, even household chores.

Vincent revered Gauguin. Gauguin found Vincent’s volatility exhausting. The tension culminated in December 1888, when Vincent, in a mental breakdown, cut off part of his ear after a heated argument.

Gauguin fled to Paris, leaving Vincent hospitalized.

The exact details remain murky. Some say it was Gauguin’s domineering presence that pushed Vincent to the edge, while others say that Vincent’s mental illness was already spiraling. Either way, Gauguin never saw Vincent again, though their brief collaboration produced some of Vincent’s most vibrant works, like Sunflowers.

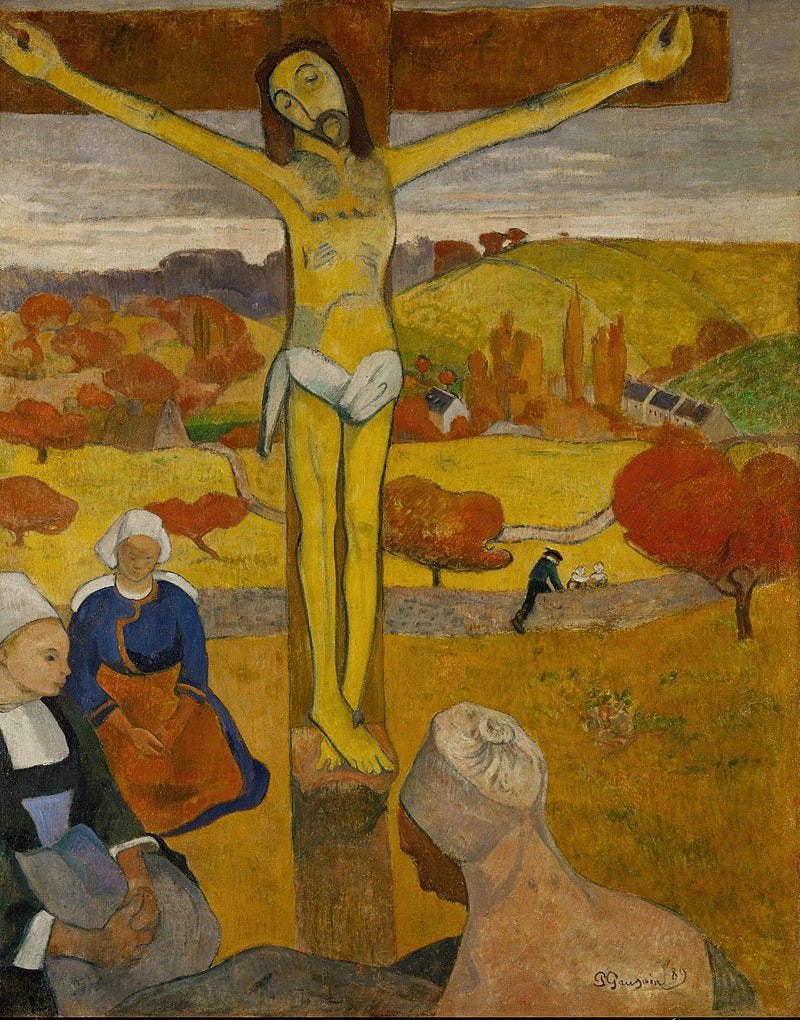

Gauguin’s paintings from Arles, like The Yellow Christ, carry traces of their shared intensity, but the episode left a stain on his reputation.

Cultural Canvas is a reader-supported publication. Every like, comment, share, or donation helps us grow—your support truly matters!

Chasing Paradise

By 1891, Gauguin was done with Europe. Disgusted by its materialism and convinced that ‘civilized’ society stifled true art, he sailed to Tahiti, seeking a mythical paradise of untouched beauty.

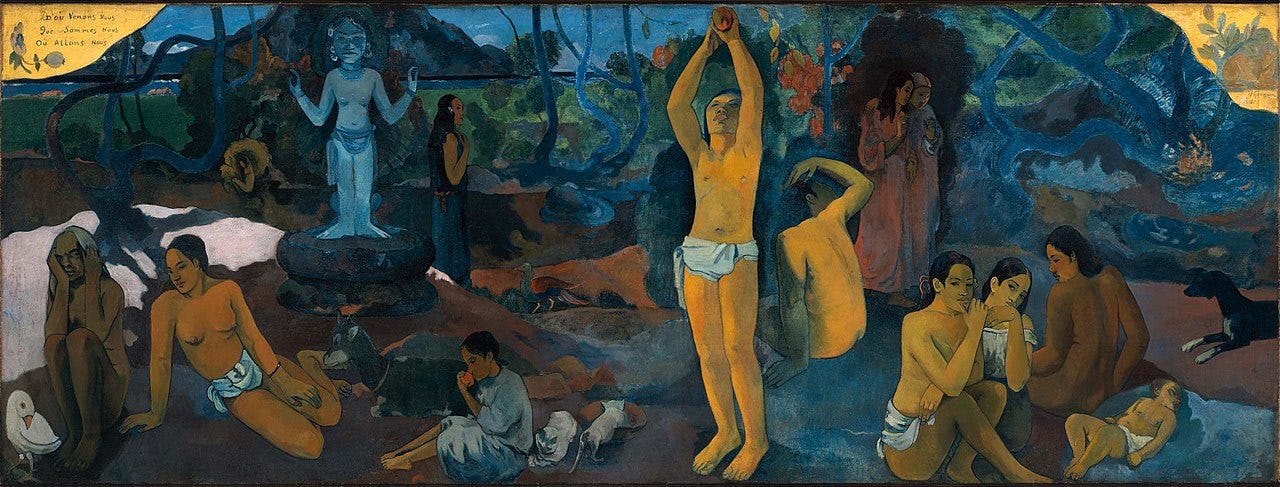

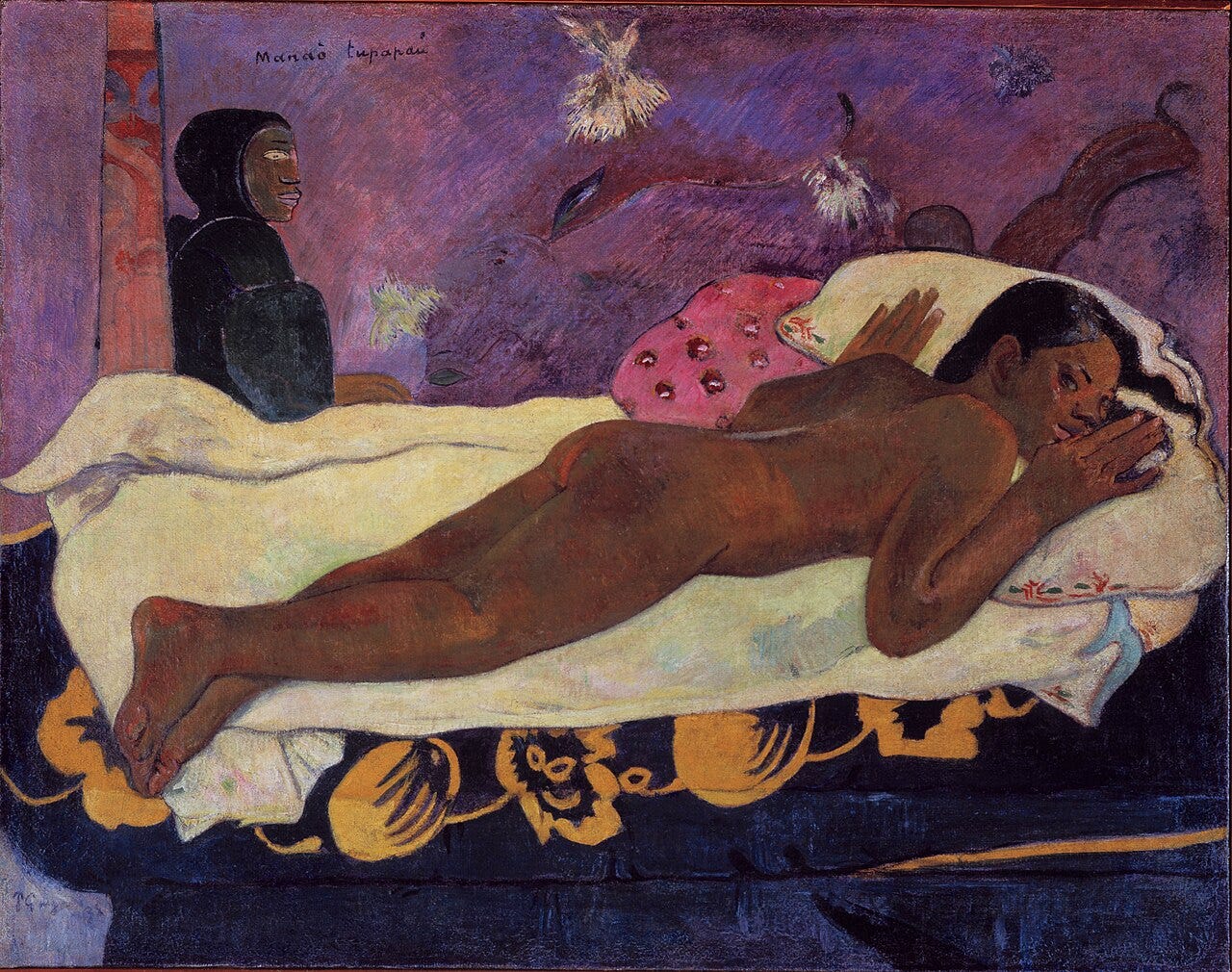

What he found was a French colony, already altered by missionaries and trade, but his imagination transformed it. His paintings from this period, like Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? (1897)—are masterpieces of color and mystery, blending Tahitian myths with his own existential questions.

Yet Gauguin’s life in Tahiti was far from idyllic. He struggled with poverty, illness (likely syphilis), and alcoholism. His relationships with local women, often young teenagers, cast a dark shadow.

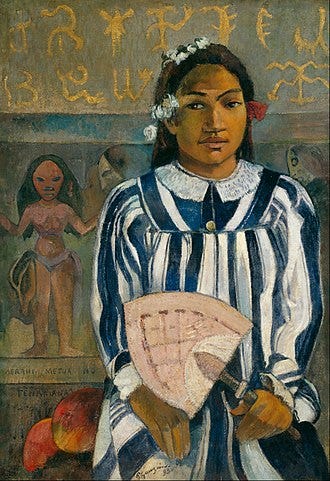

He married several Tahitian girls, including Tehamana, who was 13 when they wed.

These relationships, often romanticized in his art as pure and primal, were exploitative, rooted in colonial power imbalances. Gauguin saw himself as a ‘savage’ escaping Europe’s corruption, but his actions mirrored the very colonialism he claimed to reject.

The Dark Side

Gauguin’s legacy is inseparable from these troubling choices. He fathered children in Tahiti, abandoning them as he had his European family.

His health deteriorated, and by 1903, he was living in the Marquesas Islands, wracked by pain and addiction. He clashed with colonial authorities, championing local rights while simultaneously exploiting the culture he idealized.

His final years were marked by legal battles, including a conviction for libel, and he died alone, aged 54, from a probable heart attack.

The art world long glossed over Gauguin’s moral failings, celebrating his vibrant canvases while ignoring the human cost.

Today, his story sparks debate. Was he a visionary who broke artistic boundaries, or a predator who cloaked exploitation in exotic fantasy?

The truth, as always, is somewhere in between.

His Legacy

Gauguin’s influence is undeniable. He inspired Picasso, Matisse, and the Fauvists, who embraced his bold colors and rejection of realism. His work helped birth modern art. Yet his life reminds us that genius often comes with a shadow. He sought paradise but found no peace, leaving behind a trail of broken relationships and unanswered questions.

On his birthday, we celebrate Gauguin’s art for its audacity and beauty, but we must also confront the man, flawed, restless, and all too human. His story is a mirror: it reflects the tension between creation and destruction, between the search for meaning and the cost of chasing it.

He painted fantasies, but lived contradictions.

Can we admire the art without excusing the artist?

Missed our last piece? Read it here ↓

Thank you for being part of Cultural Canvas! If you love what we do, consider supporting us to keep it free for everyone. Stay inspired, and see you in the next post!