A mother. Her face a map of quiet devastation, cradling the body of her son—not in the warmth of life, but in the cold of death.

This is the Pietà, one of the most enduring images in Western art: the Virgin Mary holding the lifeless Christ after the Crucifixion. It’s a scene that whispers. And in that whisper lies an invitation to confront the raw ache of loss, the fragility of the divine made human.

From the shadowed chapels of medieval Germany to the sunlit niches of Renaissance Rome, the Pietà has been sculpted again and again, each version a fresh wound, a new meditation on grief.

Why does this motif persist?

Because it mirrors our own unspoken sorrows, turning stone into something alive.

The story begins not in Italy’s marble halls, but in the damp forests of Northern Europe, around the late 13th century. There, amid the Black Death’s shadow and the fervor of late Gothic piety, the Pietà—known in German as Vesperbild, evoking the evening prayer of lamentation—emerged as a devotional powerhouse.

These early sculptures were raw, unsparing.

Take the Röttgen Pietà, carved around 1300–1325 from limewood in the Rhineland. Mary sits, her veil slipping like a sigh, her features twisted in a grimace of horror. Christ sprawls across her lap, his body a grotesque parody of the infant she once nursed. It’s visceral agony, designed to pierce the viewer’s soul during the Stabat Mater liturgy, where Mary’s sorrows were enumerated like beads on a rosary.

Hundreds of such Vesperbilder survive, from the tender limestone Pietà at the Cloisters in New York (c. 1400) to the anguished wood carvings of Bohemia.

They remind us that medieval art was about empathy, not classical poise, forcing us to feel the spear in Mary’s heart as our own.

Donatello’s take

By the 15th century, as the Renaissance stirred in Italy, the Pietà migrated south, shedding some of its Gothic frenzy for a more composed grace. Donatello gave it new life. His Imago Pietatis, often referred to as the wooden Pietà, is a deeply moving sculpture created around 1450 for the high altar of the Basilica of Saint Anthony in Padua. Though often mistaken for wood due to its expressive texture, the piece is actually bronze. It depicts the dead Christ tended by angels, a rare and emotionally raw interpretation of the Pietà theme that diverges from the more traditional Virgin-and-Christ compositions.

Meester van Rimini’s

Donatello’s angels cradle Christ with human tenderness, while Rimini’s Mary holds him in frozen anguish. One turns inward, the other remains suspended in grief.

Meester van Rimini’s distills grief into alabaster. This small devotional sculpture replaces grandeur with intimacy. Mary cradles Christ’s angular body with frozen tenderness—her sorrow stylized, almost crystalline.

Unlike the swelling emotion of Gothic altarpieces or the softened grace of Renaissance Pietàs, Rimini’s version is taut, private, and arrestingly still.

Michelangelo’s

But no Pietà looms larger in reputation than Michelangelo’s. Commissioned in 1498 by the French cardinal Jean de Bilhères for his tomb in Old St. Peter’s Basilica, it was completed by the 23-year-old in under two years from a block of Carrara marble.

Mary, improbably youthful—her face smooth as a girl’s, symbolizing eternal purity—holds the adult Christ like a sleeping child, his body limp yet idealized, muscles softly defined even in death. The drapery clings with wet translucence. It’s the only work Michelangelo ever signed, after a rival claimed authorship, a rare flash of youthful vanity from a man who would later shun such gestures.

Cultural Canvas is a reader-supported publication. Every like, comment, share, and donation helps us grow—your support truly matters!

Contrary to popular belief, Michelangelo did not invent the Pietà motif. He borrowed it. What he did have, however, was the full weight of Vatican patronage behind him: a grand PR machine that elevated his version to iconic status, often at the expense of other, arguably more emotionally resonant interpretations.

In my view, Michelangelo’s Pietà is far from the most powerful ever made. It’s serene, yes—but almost too polished, too idealized.

Inside the basilica, it’s surprisingly unassuming, often passed by unnoticed. Unlike Bernini’s Baldachin or Tomb of Pope Alexander VII, sculpted by Bernini, Michelangelo’s Pietà doesn’t dominate the space—it whispers, and sometimes that whisper gets lost.

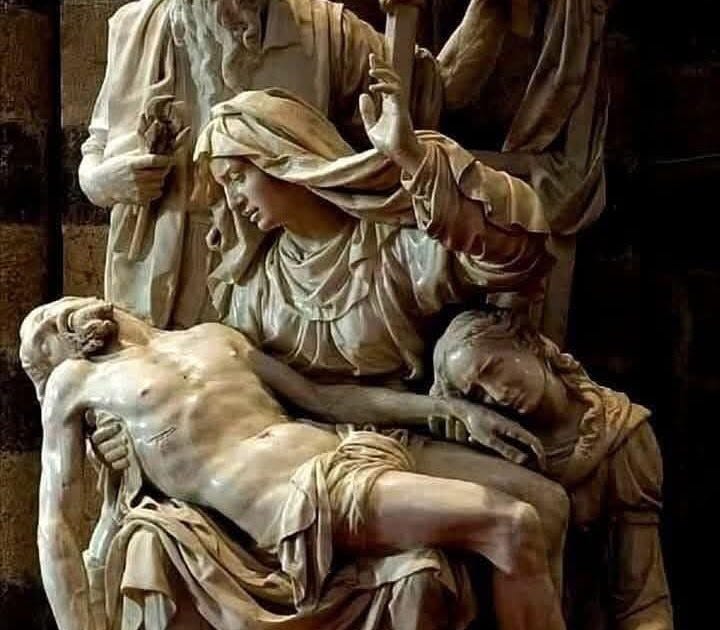

Ippolito Scalza’s Pietà

Ippolito Scalza’s Pietà (1570–1579) in Orvieto is a personal favorite. Hewn from one vast marble block, it expands the duo into a quartet: Mary, Christ, a veiled Magdalene, and Nicodemus—Scalza himself, kneeling in self-portrait, his face lined with contrition.

Christ’s body drapes heavily, wounds vivid. Mary’s gaze meets ours with pleading intensity.

Michelangelo didn’t stop at one. In his later years, as mortality gnawed, plagued by doubts, sculpting his own tomb, he returned to the Pietà, each a darker reckoning.

The Bandini Pietà (c. 1547–1555)

Rondanini Pietà (1555–1564), his last, unfinished work, is a ghost: forms emerge raw from marble, Mary straining to lift her son, their bodies merging in a desperate, abstract embrace.

As the Baroque unfurled, the Pietà grew theatrical. Yet for all its evolutions, the Pietà remains stubbornly intimate.

Why do we keep carving it?

Perhaps because grief, like faith, demands form. As the Röttgen Mary wails and Michelangelo’s gazes serenely ahead, they remind that sorrow it’s carried.

And in that carrying, we find not just pity, but the faint pulse of hope.

Thank you for being part of Cultural Canvas! If you love what we do, consider supporting us to keep it free for everyone. Stay inspired and see you in the next post!

Throughout my life, I’ve never appreciated this art in such a primal way. As a mother, I’ve felt the depth of pain that is portrayed in these works. I will never look at this art in the same way.

Grief and loss are as much with us as joy and play. We cannot avoid them, having a symbol of them, may make it easier to understand and accept them.