Hello, Dear Reader

In the rolling hills of the Périgord region in Dordogne, France, lies a monument to human creativity that predates the pyramids, the Parthenon, and even the written word!

The Lascaux Cave, often called the Sistine Chapel of Prehistory, is a testament to the ingenuity and artistry of our Paleolithic ancestors, who, some 21,000 years ago, transformed a subterranean world into a gallery of breathtaking parietal art.

On September 12, 1940, four teenagers—Marcel Ravidat, Jacques Marsal, Georges Agniel, and Simon Coencas—stumbled upon this hidden world near Montignac.

Chasing Ravidat’s dog, Robot, into a hole uncovered by a fallen tree, they discovered a cavern adorned with vivid paintings of bulls, horses, and deer, revealing one of the 20th century’s greatest archaeological finds.

A Masterpiece Underground

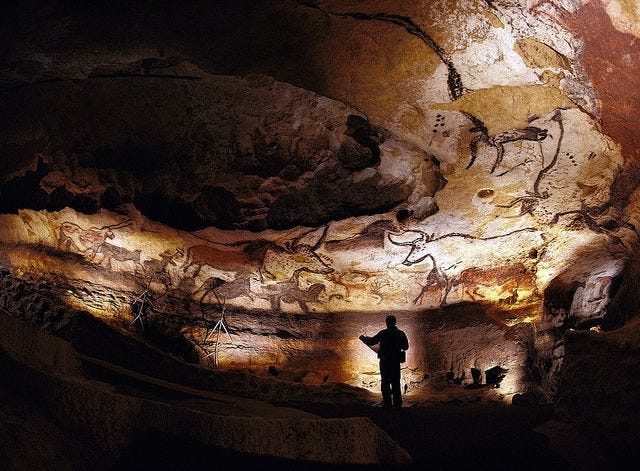

Lascaux’s nickname, the Sistine Chapel of Prehistory, is no hyperbole. Like Michelangelo’s Vatican masterpiece, its canvas is monumental—not a vaulted ceiling but the undulating limestone walls of a cave.

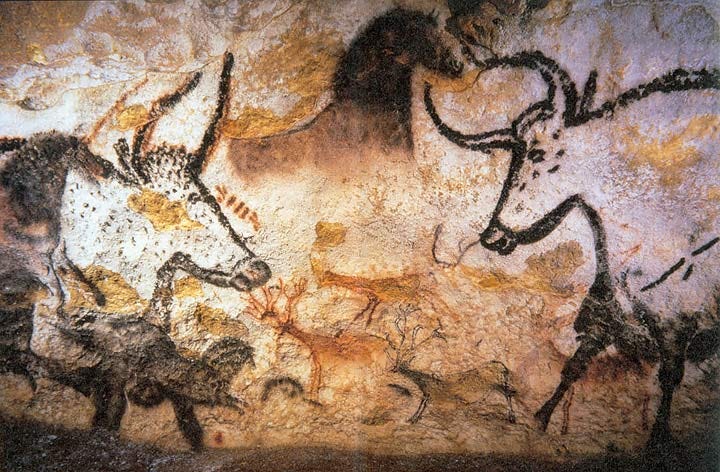

The Great Hall of the Bulls, a highlight, features massive aurochs—extinct wild cattle—stretching up to 17 feet, painted with charcoal and ochre.

These creatures charge across the rock, their forms amplified by the cave’s natural contours, as if the artists coaxed the stone to life.

The palette, crafted from minerals like iron oxide and manganese, retains a startling vibrancy, showcasing the chemical ingenuity of these ancient painters.

What compels Lascaux’s enduring intrigue is its mystery. Why did these people, living in a harsh world of survival, pour such effort into art?

The cave’s 250 meters of galleries, including the Axial Gallery and Passageway, brim with over 2,000 figures—horses, stags, ibexes, and abstract symbols like dots and grids.

Some think the cave was a sacred space for rituals or shamanic visions, bridging human and spiritual realms. Others see it as a communal gallery for storytelling or celebrating hunts. The enigmatic Unicorn, a chimeric creature with two straight horns, and the Shaft Scene, showing a fallen man beside a bison and a bird, hint at lost mythologies or narratives of death and trance.

Cultural Canvas is a reader-supported publication. Every like, comment, share, and donation helps us grow—your support truly matters!

Artistic Genius of the Paleolithic

The technical skill of Lascaux’s artists is staggering. They built scaffolding to reach high surfaces, crafted sandstone lamps for light, and pioneered airbrushing by blowing pigment through hollow bones.

Their paintings demonstrate perspective—overlapping figures for depth—and a keen grasp of anatomy, with animals’ muscles and movements rendered vividly.

A tumbling horse, legs akimbo, captures motion like a proto-animation.

The cave’s acoustics, amplifying sound in certain chambers, suggest that chants or music may have enriched the experience, immersing viewers in a multisensory spectacle.

A Fragile Legacy

Lascaux’s story is also one of fragility. Opened to the public in 1948, it drew over a million visitors by 1963, but human breath and light spurred mold and fungi, endangering the art.

Closed to the public, Lascaux II, a partial replica, opened in 1983, followed by Lascaux IV in 2016, a near-perfect facsimile at the International Centre for Parietal Art. Using laser scans and resin molds, this 8,500-square-meter complex recreates every detail with millimeter precision, blending augmented reality and 3D projections to preserve the original, now under strict scientific watch due to microbial threats.

Fascinating Fragments

Lascaux abounds with intriguing details. Hand stencils suggest women may have been among the artists. The absence of human portraits, only stylized figures, hints at cultural taboos or reverence for anonymity.

A lone red dot in an inaccessible spot might mark ritual or whimsy.

Dated to 21,500–21,000 years ago via the LasCo project, Lascaux aligns with the Magdalenian culture.

Lascaux III, a traveling exhibition, has shared its art with cities like Tokyo and Chicago, spreading its wonder globally.

A Mirror of Humanity

Lascaux humbles us, proving art is not a modern invention but a primal human impulse, born in darkness and lit by flickering lamps. The Périgord’s Sistine Chapel reflects our ancestors’ creativity and our enduring need to create.

Standing in Lascaux IV, gazing at a bull painted 21,000 years ago, we feel the pulse of humanity—persistent, ingenious, and forever drawn to beauty.

With wonder,

Muse

Missed our last story? Read it here↓

Don’t miss the newest episode of our podcast!

Thank you for writing this. I visited Lascaux 2 in the 1980s. It was a bare-bones type of visit, not touristy at all. And that was a good thing as it made me look at the paintings without a mediator. I kept wondering: How did they do that? Then, the sheer wealth of detail is impossible to describe, but it makes for a humbling experience - to know that artistic talent and the artist's love of the image is not confined to certain salons in New York, Paris, or London. The reality is how the river of art has flowed for millenia, and it invites us still to take a step into the flow.

Truly amazing artifact, on so many levels, I have written numerous poems set in this incredible place. 🌞 great post