Hello, Dear Reader

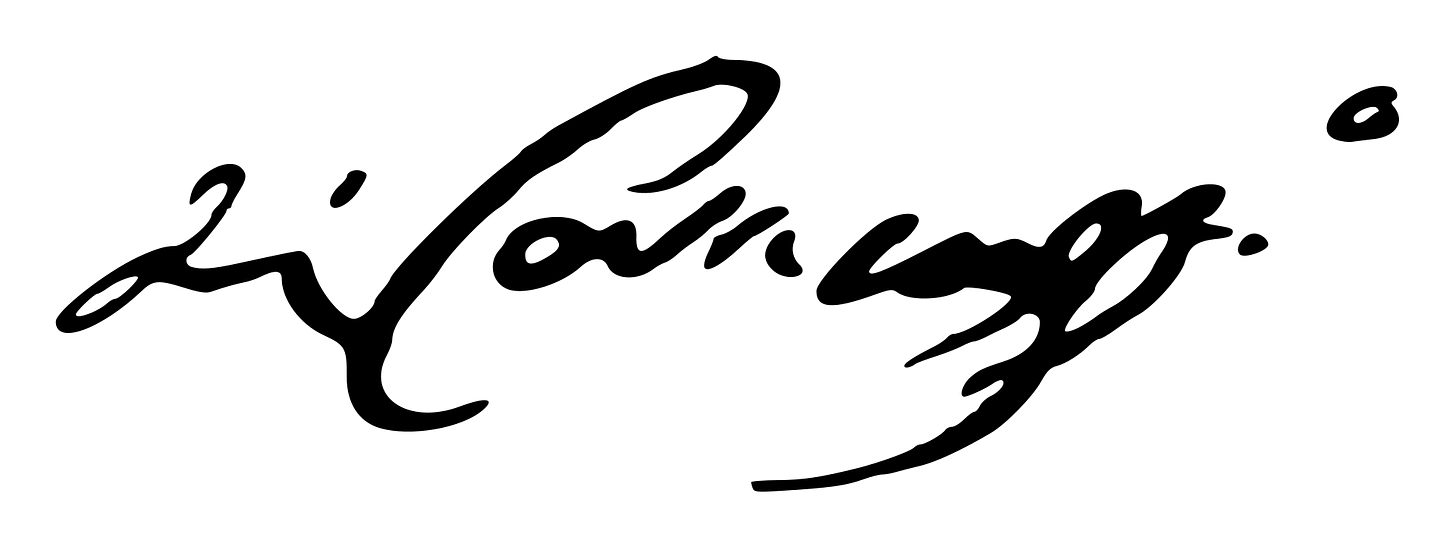

Caravaggio is a name that conjures drama—both in his art and his turbulent life.

His paintings’ visceral realism and emotional intensity changed Western art forever.

He was a man of contradictions, a visionary who painted divine scenes while living a life of violence, exile, and defiance.

Let’s dive into the life, work, and legacy of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, exploring not just the masterpieces but the lesser-known works, the myths, and truths.

The Man Behind the Myth

Born in Milan in 1571, Caravaggio’s early life was shaped by loss and instability. The plague claimed his father and grandfather when he was just six, leaving him in a world of uncertainty. By his teens, he was apprenticing under Simone Peterzano, but Milan’s provincial art scene couldn’t contain his ambition.

By 1592, Caravaggio fled to Rome—possibly after a violent altercation—an early hint of the tempestuous nature that would define him.

In Rome, Caravaggio scraped by, painting for small commissions until he caught the eye of Cardinal Francesco Maria del Monte, a cultured patron with a taste for bold art. This relationship was a turning point, granting Caravaggio access to elite circles and the means to create his early masterpieces. But even so, his behavior kept him on the edge of ruin.

The Revolution of Chiaroscuro

Caravaggio’s art was a rebellion against the idealized, polished style of the Renaissance.

While artists like Raphael painted serene Madonnas, Caravaggio brought grit to the canvas. His use of chiaroscuro, the dramatic interplay of light and shadow, was a philosophy.

Light in his paintings doesn’t merely illuminate. It reveals, accuses, and sanctifies.

Take The Calling of Saint Matthew (1600), a masterpiece in Rome’s Contarelli Chapel. Here, Christ’s outstretched hand, bathed in a shaft of divine light, summons a tax collector from his shadowy, mundane world. The scene feels like a snapshot of a real moment—Matthew’s hesitation, the grimy details of the tavern, the raw humanity.

This was Caravaggio’s gift: making the sacred feel immediate, as if it could happen in a back alley.

But his realism wasn’t always celebrated. Many accused him of irreverence. His Madonna di Loreto (c.1604), showing the Virgin Mary as a barefoot, weathered woman greeting pilgrims, scandalized those who expected ethereal divinity.

His models were often prostitutes or laborers, a choice that blurred the line between holy and profane—a line Caravaggio seemed to revel in crossing.

Lesser-Known Works and Hidden Depths

While Judith Beheading Holofernes or The Supper at Emmaus are very well-known masterpieces, Caravaggio’s lesser-known works reveal his range.

Consider The Tooth Puller (c. 1609), a grimly comic scene attributed to Caravaggio, though its authorship remains debated. It showcases a fascination with the grotesque and the everyday. Its raw physicality—blood, sweat, and pain—feels like a precursor to modern realism.

Another overlooked gem is Saint John the Baptist in the Wilderness (c.1604), one of several versions he painted. Unlike the heroic depictions of the saint by others, Caravaggio’s John is a brooding, almost melancholic figure, half-naked and vulnerable.

Then there’s The Entombment of Christ (1604), a work that balances theatricality with profound grief. The figures, arranged like actors on a stage, seem to lean out of the canvas, pulling the viewer into their sorrow.

It’s a masterclass in composition, yet it’s often overshadowed by works like Bacchus or David with the Head of Goliath.

Cultural Canvas is a reader-supported publication. Every like, comment, share, and donation helps us grow—your support truly matters!

The Dark Side of Genius

Caravaggio’s life was as dramatic as his paintings. He was a man who lived on the edge. Arrest records paint a picture of a hothead: he threw a plate of artichokes at a waiter, attacked a notary over a romantic rivalry, and carried a sword without a permit. In 1606, he killed Ranuccio Tomassoni in a duel—possibly over a debt or an insult—and fled Rome as a fugitive.

Exile took him to Naples, Malta, and Sicily, where he continued to paint masterpieces like The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist (1608), a massive altarpiece that’s both a cry for redemption and a testament to his skill.

In Malta, he briefly joined the Knights of Saint John, only to be expelled after another violent incident.

His final years were a desperate flight, marked by paranoia and illness, until his mysterious death on 18 July 1610 at age 38—possibly from fever, poison, or murder.

Caravaggio’s flaws make him a polarizing figure. To some, he was a thug who squandered his talent, and to others, his defiance of convention—both in art and life—made him a proto-modern rebel.

To the Church, he was a troublesome genius whose religious works were both a gift and a headache. Patrons like Cardinal del Monte saw him as a visionary, willing to overlook his scandals for the sake of his art. His rivals, like Giovanni Baglione, loathed him—Baglione’s biography of Caravaggio is a deliciously spiteful read.

Art historian Andrew Graham-Dixon argues Caravaggio’s paintings were deeply spiritual, using light as a metaphor for grace. Others, like Francine Prose, see him as a chronicler of human imperfection, painting saints who look like sinners because that’s what he knew.

Both celebrated and reviled

After his death, his influence waned as Baroque art moved toward grandeur. But the 20th century rediscovered him. Today, he’s an icon, his name is synonymous with drama and rebellion because his art wasn’t just about beauty but about truth as he perceived it—messy, uncomfortable, and human.

He painted saints with dirty feet, martyrs with real pain, and gods with flawed bodies.

He was unafraid to explore the fringes of human experience.

Caravaggio wasn’t a hero or a villain—he was a man who painted the world as he saw it, shadows and all.

Beauty need not be pristine. And truth, rarely is.

Missed our last story? Read it here↓

Don’t miss the newest episode of our podcast!

Thank you for being part of Cultural Canvas! If you love what we do, consider supporting us to keep it free for everyone. Stay inspired and see you in the next post!

Best analysis of Caravaggio I’ve ever read. Thank you!

Great thread muse!