The Contradictory Prophet of Modernity

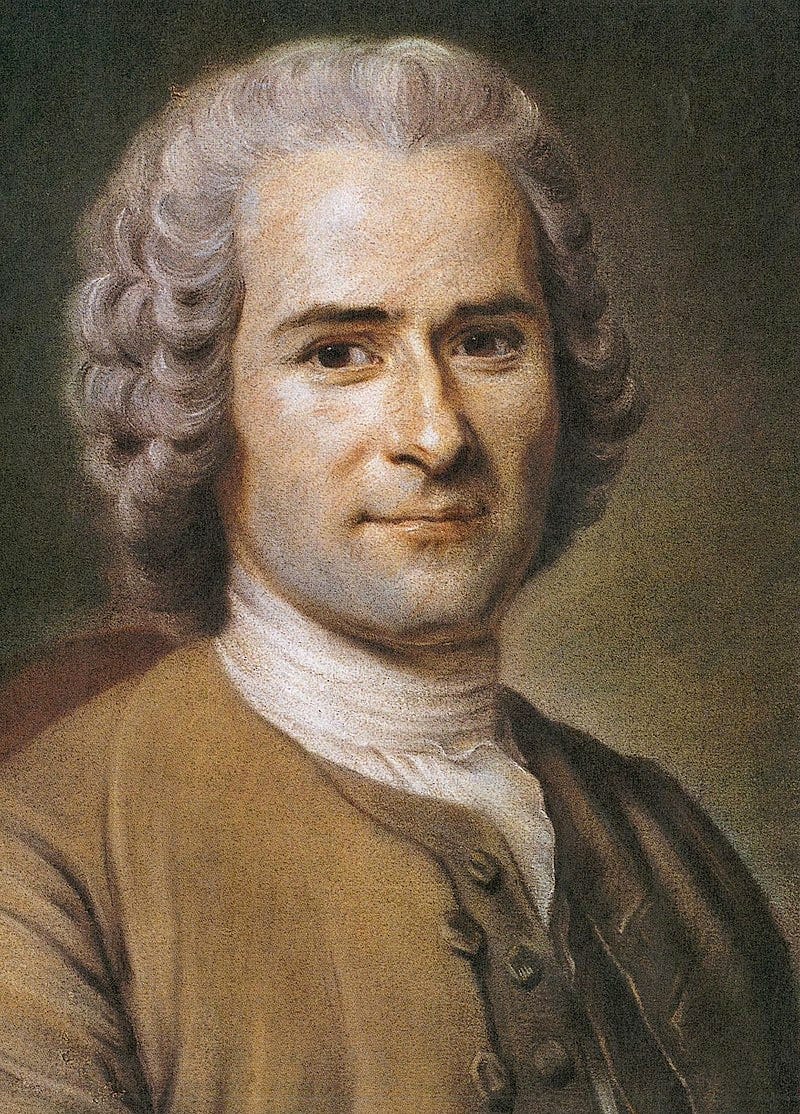

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

This exploration of Jean-Jacques Rousseau—philosopher, novelist, and provocateur—seeks to unravel the man behind the ideas that shaped the modern world.

Expect no hagiography here. We’ll probe his brilliance, his flaws, and the messy contradictions that make him so enduringly fascinating.

Let’s journey through the life, thought, and legacy of a figure who was both visionary and deeply troubled.

The Man Who Walked Alone

Born in Geneva in 1712, Jean-Jacques Rousseau entered the world under a shadow. His mother died days after his birth, and his father, a watchmaker with a penchant for romanticism, abandoned him at age ten. Raised by relatives, young Rousseau developed a fierce independence, a love for reading, and a suspicion of authority that would define his life.

By sixteen, he was a wanderer, apprenticing, drifting, and eventually landing in Paris, the intellectual crucible of the Enlightenment.

His early years read like a picaresque novel: he charmed aristocrats, converted to Catholicism (then back to Protestantism), and fell in love with music, composing operas that earned him modest fame. But beneath the surface was a man plagued by insecurity and alienation. He described himself as

“born with a natural repugnance to society,” yet craved its approval.

This tension between solitude and connection, nature and civilization, became the heartbeat of his philosophy.

The Radical Vision

Rousseau burst onto the intellectual scene in 1750 with his Discourse on the Arts and Sciences, a provocative essay arguing that progress—scientific, cultural, technological—had corrupted humanity. Where Enlightenment thinkers like Voltaire celebrated reason and refinement, Rousseau saw chains.

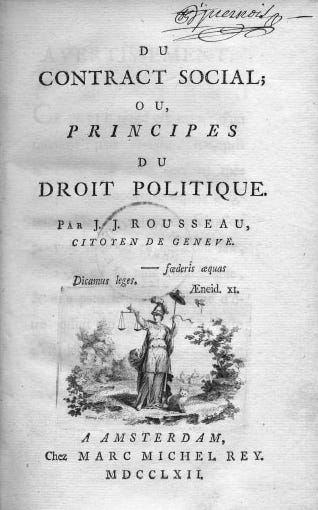

“Man is born free,” he famously declared in The Social Contract (1762), “and everywhere he is in chains.”

For Rousseau, society’s institutions, property, hierarchy, and even politeness stifled our natural goodness.

His ideas were revolutionary.

In Emile, or On Education (1762), he envisioned a child raised free from societal dogma, learning through experience in harmony with nature. In The Social Contract, he proposed a radical democracy where citizens surrender individual rights to the ‘general will’—a collective expression of shared freedom.

These works inspired the French Revolution, modern education, and even romanticism’s worship of emotion and wilderness.

But let’s pause.

Rousseau’s ‘noble savage’ myth that pre-civilized humans were pure and uncorrupted oversimplified history. Anthropologists later showed that early societies were often violent and complex, not idyllic Edens.

And his ‘general will’?

It’s a slippery concept. Critics like Edmund Burke warned it could justify tyranny, as it did when Robespierre invoked it to guillotine dissenters during the Reign of Terror.

Rousseau’s vision of freedom, while intoxicating, could curdle into coercion.

The Personal Paradox: Genius or Hypocrite?

His Confessions (published posthumously in 1782) is a raw, unflinching autobiography—perhaps the first of its kind. In it, he lays bare his soul: his insecurities, his passions, his sins. He admits to stealing, lying, and even abandoning his five children with his partner, Thérèse Levasseur, at a foundling hospital.

“I trembled at the thought of entrusting them to her family,” he wrote, justifying the act.

Yet this champion of education and natural virtue discarded his own offspring without a backward glance.

Was Rousseau a hypocrite?

His defenders say he was honest about his flaws, a man wrestling with his own contradictions in an unforgiving world. Critics, however, see a pattern of self-justification. He preached equality but lived off the patronage of aristocrats. He extolled family yet neglected his own. His relationships with friends like Diderot and Hume often ended in bitter feuds, fueled by his paranoia and sensitivity to perceived slights.

Rousseau’s personal life invites scrutiny because his philosophy was so autobiographical. He didn’t just theorize about nature and freedom—he claimed to embody them.

In his later years, he retreated to the countryside, botanizing and writing, styling himself as a solitary sage. Yet even here, he was performative, crafting a public image of authenticity that felt, to some, like a pose.

Cultural Canvas is a reader-supported publication. Every like, comment, share, and donation helps us grow—your support truly matters!

The Cultural Lens

In art, he birthed romanticism’s obsession with emotion and nature. Wordsworth’s poetry, Caspar David Friedrich’s misty landscapes, even Thoreau’s Walden—all echo Rousseau’s reverence for the sublime and the individual soul. His emphasis on childhood innocence shaped modern education, from Montessori to progressive pedagogies that prioritize creativity over rote learning.

Politically, his legacy is thornier.

The French Revolutionaries hailed him as a prophet, but his ideas also fueled totalitarianism. The ‘general will’ resurfaced in 20th-century ideologies that crushed dissent in the name of collective unity.

Yet Rousseau also inspired democratic ideals. His belief that legitimacy flows from the people, not kings, underpins modern notions of sovereignty.

From another angle, Rousseau’s critique of civilization resonates today.

In an era of crises and digital overload, his call to return to simplicity feels prescient.

Movements like minimalism or ‘rewilding’ carry his DNA, even if they don’t name him. But his distrust of progress clashes with the tech-driven optimism of Silicon Valley.

Would Rousseau see our AI age as liberation—or another layer of chains?

The Contrarian View: Was Rousseau Overrated?

Not everyone buys the Rousseau hype. Voltaire, his contemporary, mocked him as a charlatan peddling sentimental nonsense. Enlightenment rationalists saw his rejection of reason as regressive, even dangerous.

Today, some scholars argue he romanticized nature to a fault, ignoring its brutality. Others question his relevance in a globalized world where individualism often trumps the collective.

There’s also the charge of narcissism.

Rousseau’s obsession with his own feelings—evident in Confessions and his reveries—can be read as self-indulgent.

In an age of social media, where oversharing is currency, his introspective style feels less radical, more proto-influencer.

And his gender views?

Problematic by modern standards. In Emile, he prescribed a submissive role for women, educated only to serve men—a stance that alienated early feminists like Mary Wollstonecraft.

The Human Rousseau

So, who was Jean-Jacques Rousseau?

A dreamer who saw through society’s veneer, or a flawed idealist whose ideas outstripped his character? Perhaps both.

His contradictions—between freedom and control, nature and artifice, self and society—mirror our own. We, too, crave authenticity in a curated world. We champion equality yet grapple with its costs. We long for connection but guard our solitude.

Rousseau forces us to ask hard questions. Is progress always good? Can we truly be free in society? Are our virtues natural or learned?

His answers weren’t perfect, but his courage to challenge the status quo endures. He was a man who dared to feel deeply in a world that prized detachment.

His ideas are inviting us to reflect on what it means to be human.

In the end, Rousseau’s life was his greatest work: messy, flawed, and profoundly real. He reminds us that genius doesn’t require perfection—just the audacity to question everything.

Missed our last story? Read it here↓

Thank you for being part of Cultural Canvas! If you love what we do, consider supporting us to keep it free for everyone. Stay inspired, and see you in the next post!

I think Rousseau is the mirror image of the Enlightement valorisation of reason, he championed what I think of as sentimental humanism, a focus on feelings without reference to reason or others.

I think this is often used in tandem with today’s corporate capitalism as a way of enslaving others….

While reading this, I felt sorry for Rousseau because he was abandoned by his parents at an early age. But this undoubtedly played a major role in defining his life and character, and as you point out, his brilliance as well as his faults. Great post!