Hello, Dear Reader

Today, we step into a world where beauty wasn’t just ornamental—it was spiritual, symbolic, and revolutionary. Before Art Nouveau became a social media aesthetic and Mucha a poster-store staple, he was a man with visions far grander than lithographs of languid women.

In this brief journey, we’ll trace the silhouette of Alphonse Mucha—not as a decorative artist, but as a mystic, patriot, and restless dreamer who saw art as a pathway to something greater.

When you hear the name Alphonse Mucha, what springs to mind?

Swirling lines, ethereal women with flowing hair, and vibrant posters that scream Art Nouveau. But Mucha was far more than a decorative artist who churned out pretty pictures.

From Humble Beginnings to Parisian Fame

Born in 1860 in Ivančice, a small town in Moravia (then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, now the Czech Republic), Alphonse Mucha grew up in a world far removed from the glamour of Paris. His father was a court usher, and money was tight.

Young Alphonse showed artistic talent early, sketching and painting in a region where art was a luxury. But his path wasn’t easy. Rejected by Prague’s Academy of Fine Arts with the brutal dismissal that he should “find another profession,” Mucha faced the kind of setback that could’ve crushed a lesser spirit. Instead, he hustled, taking on odd jobs like painting theater sets and portraits for local bigwigs.

His big break came through a stroke of luck in 1885, when Count Karl Khuen-Belasi, a wealthy patron, spotted Mucha’s talent and funded his studies in Munich and Paris.

By the late 1880s, Mucha was in the French capital, scraping by as an illustrator while soaking up the bohemian energy of Montmartre.

Then, in 1894, fate intervened.

Sarah Bernhardt, the most famous actress of her time, needed a poster for her play Gismonda. Mucha, in the right place at the right time, delivered a design that was unlike anything Paris had seen: tall, elegant, with soft colors and intricate details, it turned Bernhardt into a near-mythical figure.

Overnight, Mucha was a star.

But he didn’t love this fame. He saw himself as a serious artist, not a commercial poster-maker. The posters that made him a household name—advertising everything from champagne to cigarette papers—were, to him, a means to an end. He once said:

“I was happy to be involved in an art for the people and not for private drawing rooms.”

He felt trapped by the very style that defined him.

The Mucha Style: More Than Meets the Eye

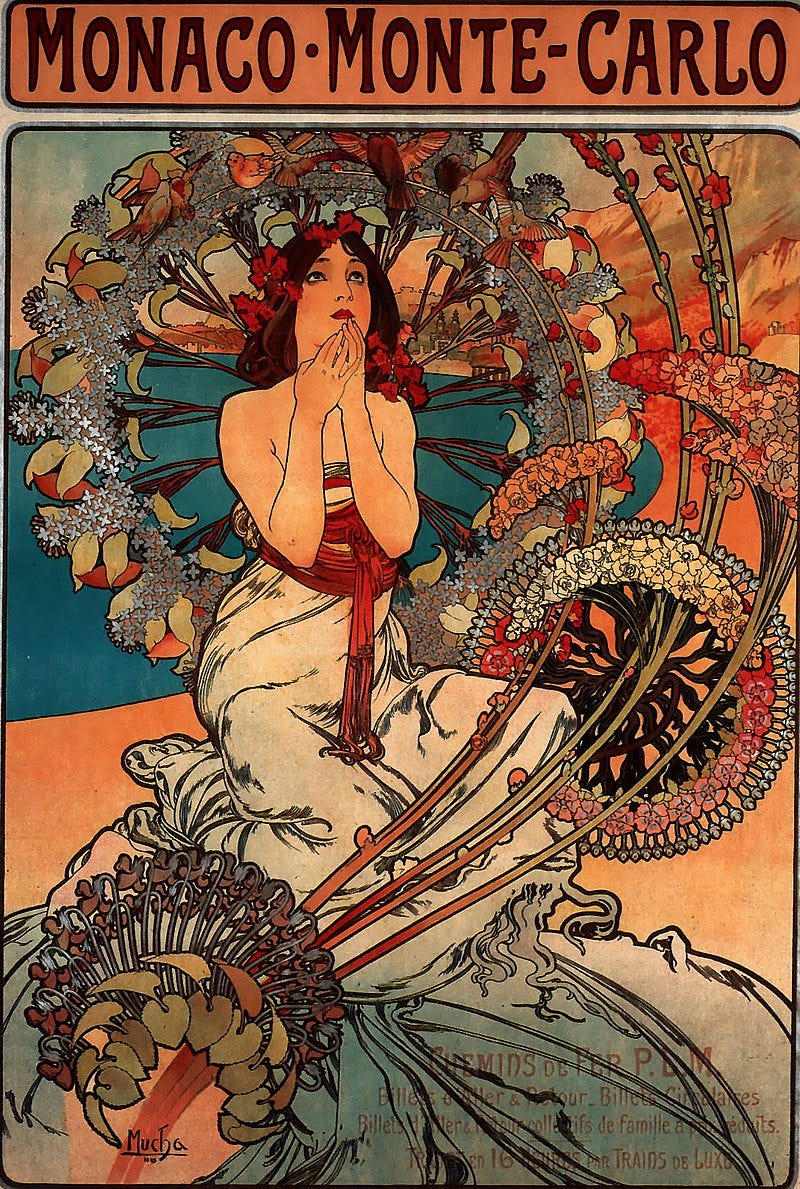

Mucha’s Art Nouveau aesthetic is instantly recognizable: flowing lines, organic forms, and a sense of harmony that feels almost otherworldly.

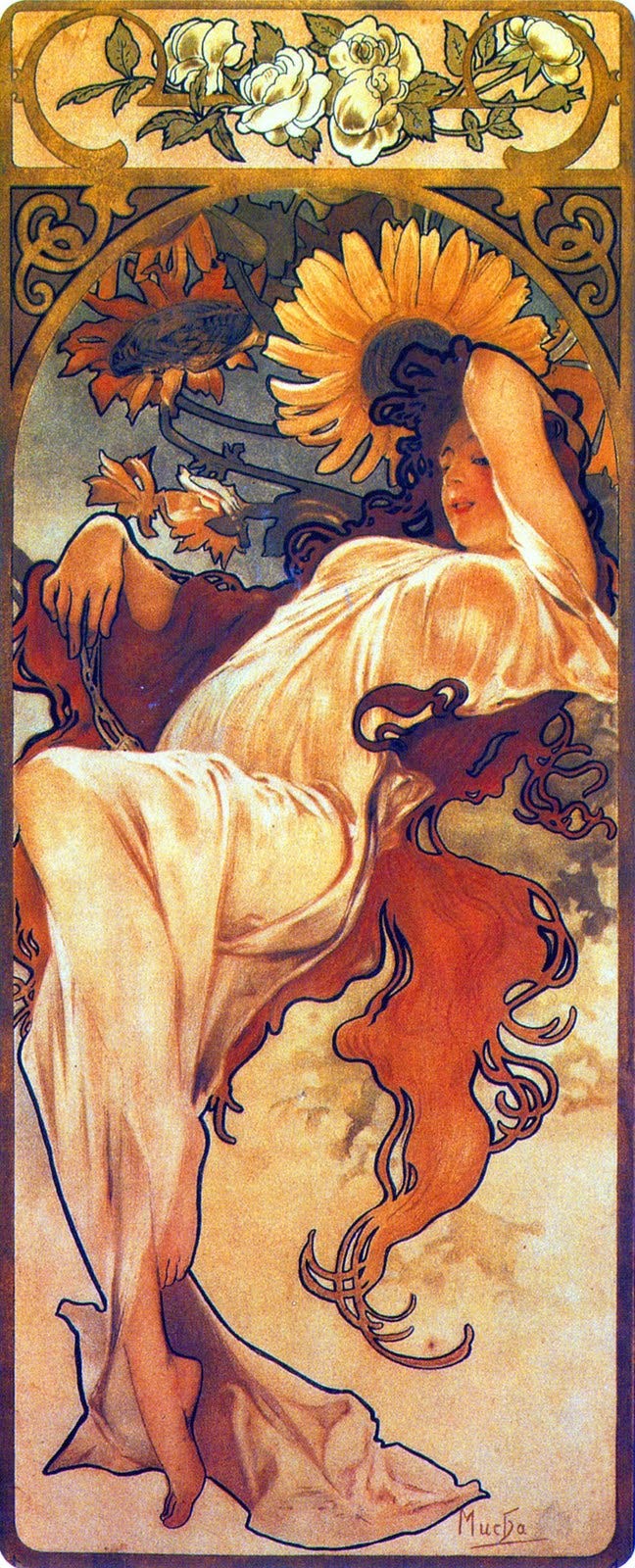

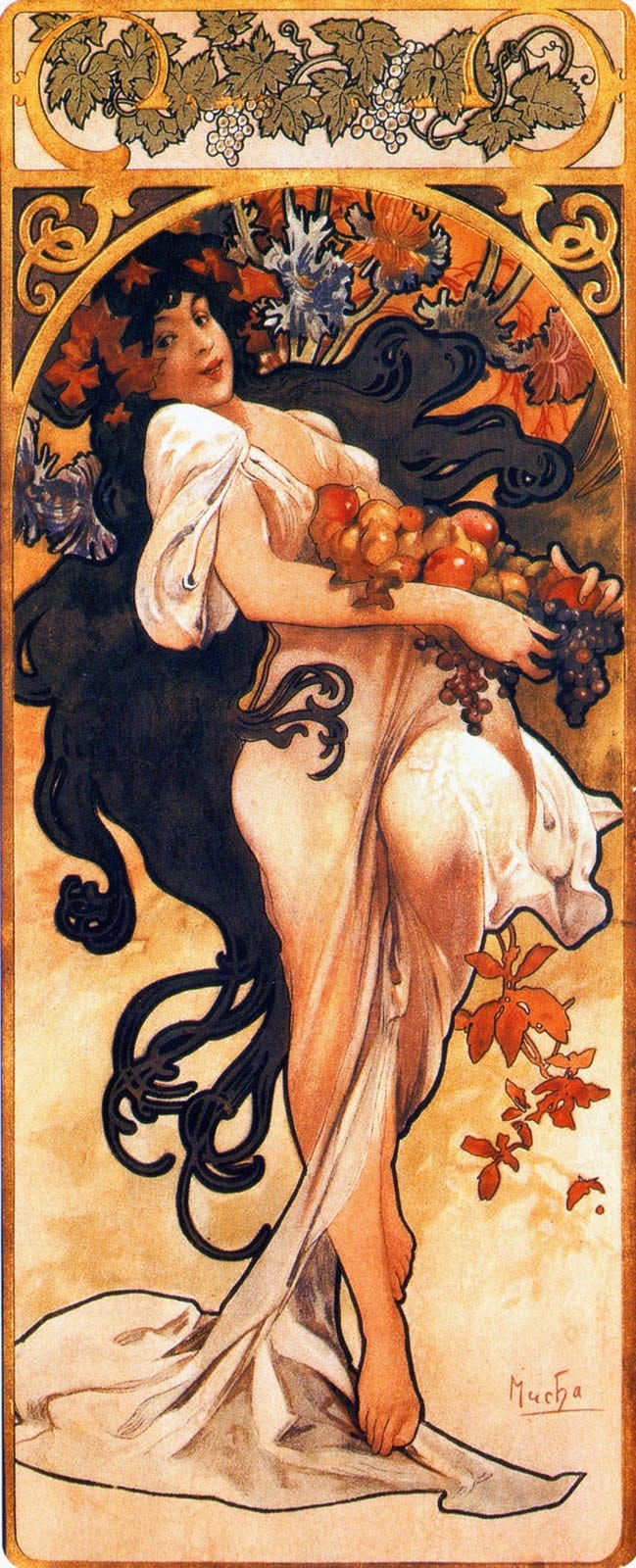

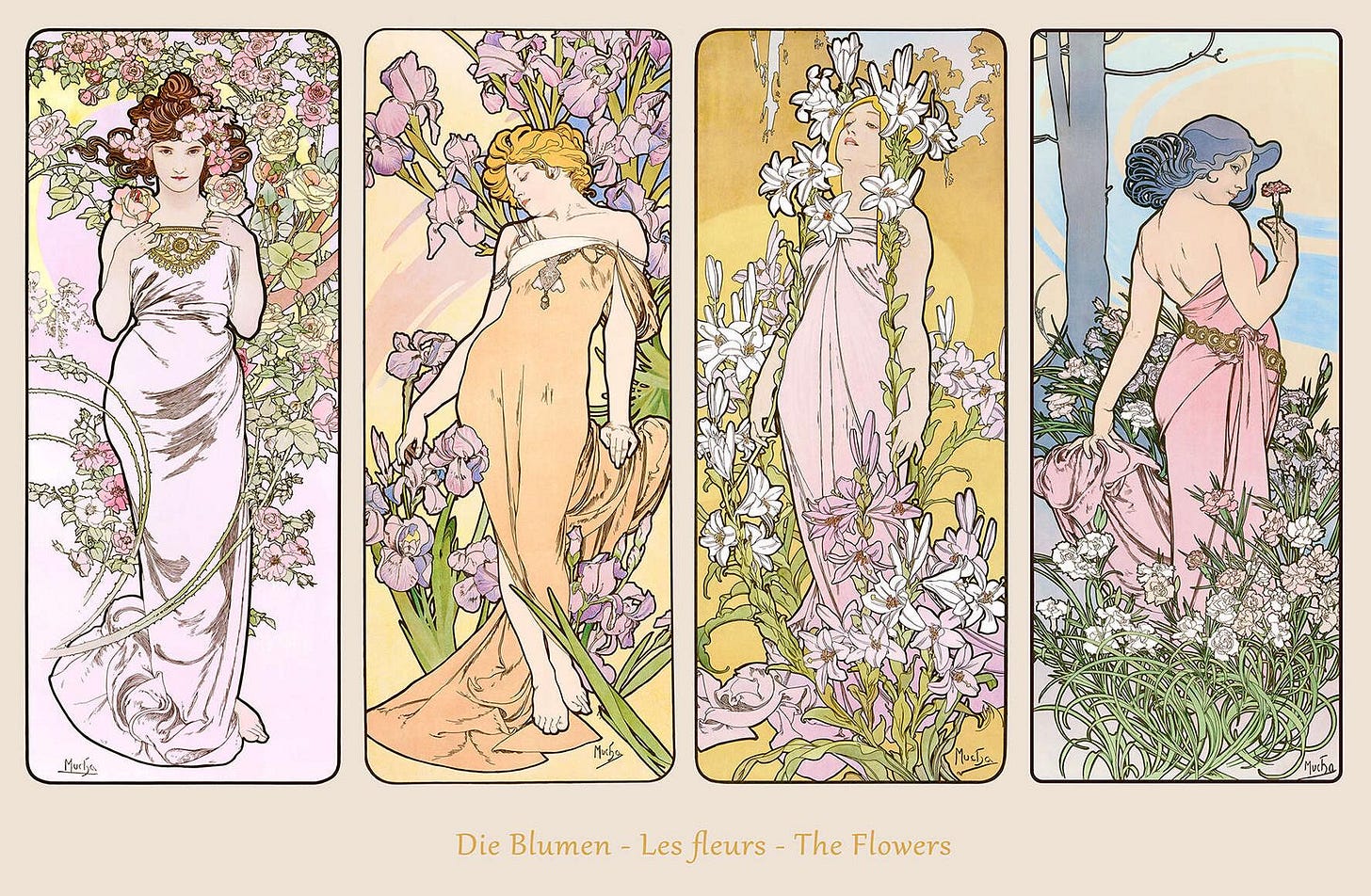

His posters, like The Seasons or The Flowers, feature women as allegorical figures, draped in diaphanous gowns, surrounded by nature-inspired motifs.

The Seasons, 1897 series

The Flowers

But what’s less discussed is how much of this came from his deep spiritual and philosophical beliefs.

Mucha was a devout mystic, influenced by Freemasonry, Theosophy, and Slavic folklore. He believed art could elevate the soul and connect humanity to the divine. His famous Le Pater (1899), a lesser-known illustrated book, was a deeply personal project where he reinterpreted the Lord’s Prayer through intricate, symbolic designs.

Unlike his commercial posters, Le Pater was a labor of love, blending Christian themes with esoteric ideas. He considered it one of his proudest achievements, yet it’s barely remembered today compared to his biscuit ads.

Another hidden gem is his work in decorative arts.

Beyond posters, Mucha designed jewelry, furniture, and even stained-glass windows, like those for St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague.

These projects reveal his obsession with Gesamtkunstwerk—the idea of a total work of art where every element, from architecture to decor, harmonizes. His designs for the Fouquet jewelry shop in Paris (now partially preserved in the Carnavalet Museum) show a man who didn’t just paint beauty but wanted to build it into the world around him.

The Slavic Epic: A Dream Deferred

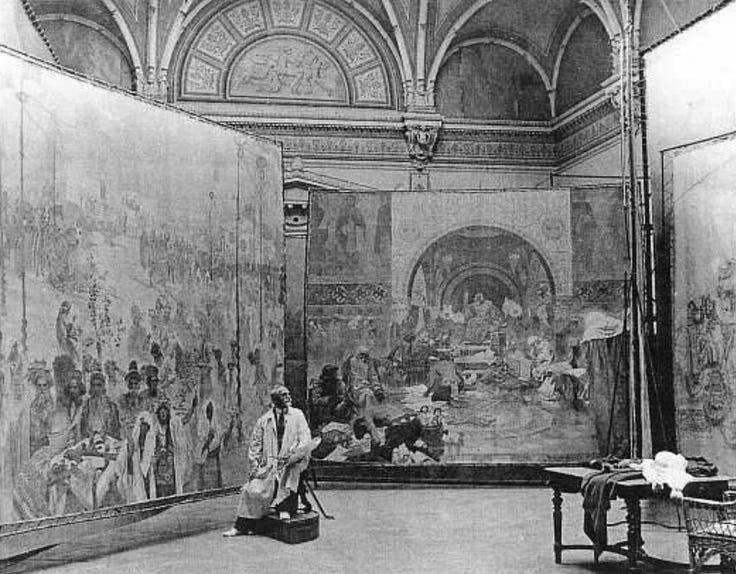

If Mucha’s posters were his public face, The Slav Epic was his heart. This monumental series of 20 massive paintings, created between 1910 and 1928, is one of the most ambitious and least celebrated projects of his career.

After achieving fame in Paris, Mucha returned to his Czech roots, driven by a patriotic desire to tell the story of the Slavic peoples.

Funded partly by American millionaire Charles Crane, the Epic depicts key moments in Slavic history, from mythical origins to modern struggles, rendered in Mucha’s signature style but on a colossal scale—some canvases are over 20 feet wide.

Cultural Canvas is a reader-supported publication. Every like, comment, share, and donation helps us grow—your support truly matters!

What’s lesser-known is the personal toll this project took. Mucha poured his fortune and health into it, working in a rented castle in Moravia. He faced criticism from Czech nationalists who thought his work too decorative and from modernists who dismissed it as outdated.

By the time he completed the Epic in 1928, Art Nouveau was passé, and Mucha was seen as outdated. The paintings were stored away, neglected, and even damaged during World War II. Today, they’re housed in Prague’s National Gallery, but their grandeur remains underappreciated outside Czechia.

The Darker Years: Struggle and Legacy

Mucha’s later life was marked by hardship. In the 1930s, as Czechoslovakia faced growing threats from Nazi Germany, Mucha’s health declined. His outspoken patriotism and Masonic ties made him a target. When the Nazis invaded in 1939, they arrested the 79-year-old artist for interrogation. Though released, the ordeal broke him, and he died of pneumonia shortly after.

His death was a quiet end for a man whose work once lit up Paris.

But there’s more to this story.

Mucha’s legacy was almost lost. After World War II, his work was dismissed as bourgeois by Czechoslovakia’s communist regime. His posters were rediscovered in the 1960s by Western counterculture, who saw in them a psychedelic vibe, but this revival often reduced Mucha to a pop-art cliche.

Only in recent decades, with exhibitions like those at Prague’s Mucha Museum, has his full range—posters, paintings, designs, and writings—been appreciated.

The Man Behind the Myth

What’s often missed about Mucha is his humanity. He was a father of two, married to Marie Chytilová, whom he met in Paris. He was a photographer, too, using early cameras to capture models, costumes, and even his own children for reference. His studio was a laboratory of ideas, filled with books on mysticism, history, and science. He was also a bit of a prankster, known to sketch caricatures of friends and sneak Czech symbols into his work as a quiet act of rebellion against Austro-Hungarian rule.

His contradictions make him fascinating.

He was a commercial artist who hated commercialism, a global star who yearned for home, a mystic who worked in a materialist age. His belief in art’s power to unite people feels almost naive today, yet it drove him to create works that still captivate.

Mucha Matters

His Art Nouveau style, with its emphasis on beauty and nature, resonates in an era craving authenticity amid digital noise.

His belief in art’s power to transcend borders and awaken the human spirit—echoes louder than ever.

He reminds us that beauty, when rooted in purpose, it doesn’t fade, it endures.

Don’t miss the newest episode of our podcast!

Thank you for being part of Cultural Canvas! If you love what we do, consider supporting us to keep it free for everyone. Stay inspired and see you in the next post!

His work is beautiful and I’d love to see his stained glass windows! A sad ending, but a fulfilling life. Wonderful post Muse!

Fantastic article